Corporate / organisational culture

The term 'corporate cultures' was introduced by Deal and Kennedy in Corporate Cultures: Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life (1982). Their book received mixed reactions with detractors saying it was a superficial application of the discipline of anthropology to management. However, since this time, the term has become an accepted part of business language and forms a key element of corporate strategy.

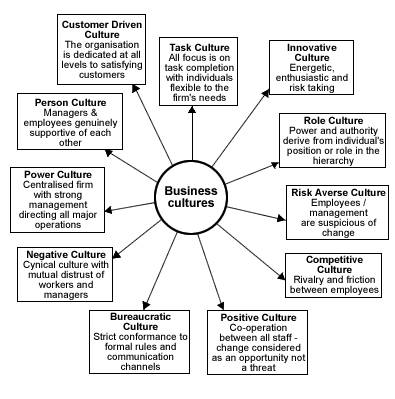

A number of studies have been undertaken to identify business culture types. Some are highlighted in figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Business culture types

There is normally a clear link between the type of corporate culture and the nature of organisational structures adopted in the firm. A power culture, for instance, requires senior managers to exercise strict control and to operate centralised decision-making. The organisation structure is likely to be tall with small spans of control.

Innovative cultures, and those that promote the role of individuals, are likely to employ flatter hierarchies with individuals within the organisation empowered to take more important decisions and to work on their own initiative.

Clearly there are also links here with motivation, selection and training. It is unlikely that individuals will be able to satisfy their higher order needs, such as their ego or social needs, in an organisation where suspicion and mistrust is endemic. Senior managers may not appoint individuals whom they perceive as long-term threats to their positions or reputations, and it may be the feeling that training is a waste of money when all major decisions are taken at the top anyway. Even more junior employees may accept the status quo when it reduces their responsibilities and where they lack confidence in approaching new tasks. If salaries are low, they may also feel that they are not paid to take important decisions.

Often a certain culture is self-perpetuating, once established. If it is accepted that management are appointed to be in control and, if autocratic management styles are expected, then even individuals newly appointed to management positions, who may not naturally possess this leadership approach may feel pressure to adapt to the demands of their new role.

However, cultures do alter over time. As the external environment changes and markets become more competitive and global, managers are forced to delegate more of their function and authority. 'New blood' brings new ideas and cultural, legal and social changes may demand the corporate culture adapts and grows.

Cultures may also change when organisations merge or when one organisation, is acquired by another. Mergers are often driven by the desire to obtain synergies and economies of scale. However, some mergers, which appear on paper to be 'made in heaven' fail in practice. Reasons often include a clash of management styles and corporate cultures. If one organisation, for instance, with a role culture merges with another with a task culture, there may be problems with expectations and with the operation of teams. Individuals may feel threatened where their traditional authority is challenged, or where they are expected to be more flexible and take on new responsibilities and challenges. What tends to happen in practice is that a new hybrid culture evolves and those who cannot adapt leave the new organisation. Alternatively, the business may crash spectacularly, or the management may feel compelled, for commercial reasons, to separate back into their component organisations.

Charles Handy: Organisational culture

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

No culture or mix of cultures, is bad or wrong in itself, only inappropriate in the circumstances.

Charles Handy

Conflicts inevitably arise when the cultures are mixed in inappropriate ways. For instance Handy describes the situation where newly formed, but quickly expanding enterprises become more Apollonian as they grow, pitting Zeus and the founders' club against a middle management dedicated to preserving order. Athenian organizations also become more rules-based as they grow, alienating employees, who would rather be judged by outcomes on specific projects than evaluated by formal appraisal procedures. Dionysians are often unmanageable by conventional means, such as perks, promotions, or the threat of dismissal; they also prefer to sell their services to a succession of highest bidders rather than accept the apparent security of a stable wage.

Handy believes that success will be found in the triumph of Athens and the formation of the of adaptable, flexible and decentralised organisation that he labelled the shamrock organisation, with the three leaves representing different groups of people with various goals, tasks, and rewards.