Topic pack - Macroeconomics - introduction

Welcome to this Triple A Learning topic pack for Macroeconomics. The pack has a wide range of materials including notes, questions, activities and simulations.

A few words about Navigation

So that you can move to the next page in these notes more easily, each page has navigation tools in a bar at the top and the bottom. These tools are shown below.

![]() The right arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the next page of content.

The right arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the next page of content.

![]() The left arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the previous page.

The left arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the previous page.

![]() The home button will take you back to the table of contents for the pack.

The home button will take you back to the table of contents for the pack.

The pack is split into a series of sections and to access each section, the easiest way is to use the table of contents on the left-hand side of the page. To return to the full table of contents, please click on the 'home button' at any stage.

Higher level extension material

Some of the material in this pack relates to the higher level extension topics in the Economics guide. This material is marked by icons as follows:

This icon indicates the start of the higher level extension material.

This icon indicates either:

- The higher level extension material continues on the next page or

- The higher level extension material continues from the previous page

This icon indicates the end of the higher level extension material.

To start viewing the contents of the pack, please click on the right arrow at the top or bottom of the page.

Key terms - the level of economic activity

One of the key things you need to be sure to know are the definitions of all key macroeconomics terms. In this section we give you explanations and definitions of terms relevant to the level of economic activity.

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Key terms - aggregate demand and supply

One of the key things you need to be sure to know are the definitions of all key macroeconomics terms. In this section we give you explanations and definitions of terms relevant to aggregate demand and supply.

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Key terms - macroeconomic objectives

One of the key things you need to be sure to know are the definitions of all key macroeconomics terms. In this section we give you explanations and definitions of terms relevant to macroeconomic objectives.

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Key terms - macroeconomic policy

One of the key things you need to be sure to know are the definitions of all key macroeconomics terms. In this section we give you explanations and definitions of terms relevant to macroeconomic policy.

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Aims of the economics course

The aims of the economics course at HL and SL are to enable students to:

- develop an understanding of microeconomic and macroeconomic theories and concepts and their real-world application

- develop an appreciation of the impact on individuals and societies of economic interactions between nations

- develop an awareness of development issues facing nations as they undergo the process of change.

Assessment Objectives

Having followed the economics course at HL or SL, students will be expected to:

- AO1 Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of specified content

- Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the common SL/HL syllabus

- Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of current economic issues and data

- At HL only: Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the higher level extension topics

- AO2 Demonstrate application and analysis of knowledge and understanding

- Apply economic concepts and theories to real-world situations

- Identify and interpret economic data

- Demonstrate the extent to which economic information is used effectively in particular contexts

- At HL only: Demonstrate application and analysis of the extension topics

- AO3 Demonstrate synthesis and evaluation

- Examine economic concepts and theories

- Use economic concepts and examples to construct and present an argument

- Discuss and evaluate economic information and theories

- At HL only: Demonstrate economic synthesis and evaluation of the extension topics

- AO4 Select, use and apply a variety of appropriate skills and techniques

- Produce well-structured written material, using appropriate economic terminology, within specified time limits

- Use correctly labelled diagrams to help explain economic concepts and theories

- Select, interpret and analyse appropriate extracts from the news media

- Interpret appropriate data sets

- At HL only: Use quantitative techniques to identify, explain and analyse economic relationships

Section Two Structure

Unit two has four core sub-topics and one HL extension.

Using the pack

Questions

At the end of the section there are a number of questions you can attempt to check your understanding of the concepts involved. When attempting a question you should always be clear about what the question is actually asking you to do. A key to doing this is to look for the command term that starts the question. This command term will tell you whether the question needs an explanation, requires some analysis or expects you to offer some insights or draw conclusions of your own. In may sound obvious but always remember that the success of passing an examination or test is to ensure that the answer you give corresponds to the question that is being asked!

Pauses for thought

Throughout the pack there will be times when you are asked to think about some issues relating to macroeconomics in a broader sense. This may involve you reflecting upon the validity of the information you have found or been given or encourage you to make connections with other areas of knowledge. You may want to talk about some of these issues with other students family members or friends as some of the ideas can be quite contentious and lead to some interesting discussions.

2.1 The level of overall economic activity (notes)

In this section, we consider the level of overall economic activity.

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Describe, using a diagram, the circular flow of income between households and firms in a closed economy with no government.

- Identify the four factors of production and their respective payments (rent, wages, interest and profit) and explain that these constitute the income flow in the model.

- Outline that the income flow is numerically equivalent to the expenditure flow and the value of output flow.

- Describe, using a diagram, the circular flow of income in an open economy with government and financial markets, referring to leakages/withdrawals (savings, taxes and import expenditure) and injections (investment, government expenditure and export revenue).

- Explain how the size of the circular flow will change depending on the relative size of injections and leakages.

- Distinguish between GDP and GNP/GNI as measures of economic activity.

- Distinguish between the nominal value of GDP and GNP/GNI and the real value of GDP and GNP/GNI.

- Distinguish between total GDP and GNP/GNI and per capita GDP and GNP/GNI.

- Examine the output approach, the income approach and the expenditure approach when measuring national income.

- Evaluate the use of national income statistics, including their use for making comparisons over time, their use for making comparisons between countries and their use for making conclusions about standards of living.

- Explain the meaning and significance of "green GDP", a measure of GDP that accounts for environmental destruction.

- Explain, using a business cycle diagram, that economies typically tend to go through a cyclical pattern characterized by the phases of the business cycle.

- Explain the long-term growth trend in the business cycle diagram as the potential output of the economy.

- Distinguish between a decrease in GDP and a decrease in GDP growth.

- Calculate nominal GDP from sets of national income data, using the expenditure approach.

- Calculate GNP/GNI from data

- Calculate real GDP, using a price deflator.

Overall economic activity - introduction

In this section, we consider the following sub-topics in detail:

In this section, we consider the following sub-topics in detail:

- Economic activity

- Circular flow of income model

- Measures of economic activity

- The business cycle

- Short term fluctuations and long term trend

Peoples' living standards are clearly dependent upon the amount of goods and services that they are able to consume. Therefore, the production and exchange of these goods and services in the economy, the level of economic activity, will directly affect peoples' wellbeing. A major aim of governments is to improve the living standards of its citizens by increasing the amount of economic activity and the rate at which this activity grows.

To get a better understanding of the nature of economic activity, we will explore a simple model of an economic system - the circular flow of income. This will enable us to see the various elements of the economy and how they relate to each other. As will all economic models, it will be based on a number of simplifying assumptions. The use of assumptions it allows us to make some simple predictions that relate to the real world.

Pause for thought

Economics is considered by many to be a social science. It uses models based on simplifying assumption as tools to help understand complex systems, and problems, and to make predictions about the real world. Is this approach used in other subjects you study? If not, why not?

A main aim of government is to increase the wealth of the economy by maintaining or increasing the level of economic growth. Economic growth is measured in terms of the increase in national income over a period of time. What do we understand by the term National Income and how do we measure it? In this section we look at the issues relating to national income and its measurement.

One of the other interesting things about economic activity is, that over time, it constantly changes. These changes can occur from year to year as the economy moves through a business cycle, but also over the longer term as the economy experiences growth or decline.

The circular flow of income model (1)

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Circular flow - two sector closed

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Circular flow - two sector open

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Circular flow - three sector open

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Circular flow - government

How important is the role of government in the economy?

In the 3-sector open economy circular flow of income, we could also represent the government separately in this circular flow - here's an alternative representation of the 3-sector open economy circular flow. It shows exactly the same flows, but represents them a little differently.

Figure 1 Circular flow - 3 sector, open economy

In this diagram, why a big box in the middle for government? Just how big a player do you think the government is in the economy?

Useful Internet sites for research are:

- The World Bank site. To access details about countries and economies, follow this link.

- The OECD statistics portal.

- Identify the proportion of national income represented by government expenditure in your country.

- Identify the proportion of national income taken up by government spending for the following countries

- USA

- Tanzania

- Sweden

- Cuba

- Hong Kong

- Considerthe differences in the proportion of national income represented by government spending in the countries above and with your country.

- Reflect on the reasons for these differences and remember these findings as you work your way through the macroeconomics pack.

The circular flow of income model (2)

In a centrally planned economy, where the government takes direct responsibility for planning, producing and distributing goods and services to the population, what will the circular flow look? Think about this, then click CENTRALLY PLANNED to see how our answer matches with yours.

Yes, this is an example of a 2-sector economy. The government is the same as firms, since all firms are owned by the government (state). However, the economy may still be open or closed.

Look again at the circular flow model for a three-sector economy.

Figure 5 Circular flow: A 3 sector, open economy

Circular flow - a summary

A reminder:

The leakages (W) from the circular flow are:

- Savings (S)

- Taxation (T)

- Purchase of imported goods and services (M) (goods and services in, but money out - national firms pay overseas ones for goods and services)

The injections (J) are

- Investment (I) - expenditure on capital goods

- Sale of exports (X) (goods and services out, but money now flows in)

- Government Expenditure (G)

An economy is in equilibrium when injections (J) match the leakages (W).

The standard codes used in this model, and in economics in general, are:

Y = National Income

C = Domestic Consumption

S = Savings

M = Imports

T = Taxation

I = Investment

X = Exports

G = Government Spending

The circular flow model of an economy is very useful within the study of economics. We will be looking at the actions and behaviour of firms and households, and how governments interact with them. We will also look at how changes in the leakages and injections affect the stability of an economy.

Some mathematics

Economists offer try to use mathematics to simplify the analysis of the circular flow of income model. Income is passed on in the circular flow of income through consumer spending or leaked out though savings, taxation or spending on imports. The proportion of national income spent on consumption is called the average propensity to consume (APC)

![]()

The proportion of national income save is called the average propensity to save (APS)

![]()

Economists have a penchant for what happens at the margin, or when variables change in an incremental way. Anytime there is an incremental change in national income consumption, savings, taxation and imports will also change by a certain proportion. Whereas average propensity is concerned with the proportion of total national income that is passed on or leaked from the circular flow of income, marginal propensity is used to describe the proportion of an incremental change in income that is passed on or leaked from the circular flow of income, .

We can, therefore, identify the marginal propensity to consume as the proportion of a change in national income that is spent on consumption

![]()

Similarly, the proportion of a change in national income that is saved, is called the marginal propensity to save (MPS)

![]()

The proportion of a change in national income that is paid to the government in tax, is called the marginal rate of taxation (MRT)

![]()

The proportion of a change in national income that is spent on imported goods, is called the marginal propensity to import (MPM)

![]()

Now have a go at the following questions:

- Assuming a two sector closed economy and that the APC = 0.6 and national income is $1000, calculate the:

- level of consumer spending

- level of savings in the economy.

- Assuming a three sector open economy and that the MPS and MRT and MPM are all 0.2, and national income changes by £2000, calculate the change in the level of:

- consumer spending

- tax revenue

- import spending

- Assuming a three sector open economy (however would also be the case for a two sector closed and open economy) the MPC is 0.5, and national income falls by £1500, calculate:

- the change in the amount of money that leaks out of the circular flow of income

- the change in the amount of consumer spending.

These concepts will be revisited later in later section when we look at what causes national income to change.

Measures of economic activity

In the last section, we looked at the circular flow of income and established that the total flow of income around the economy arising from economic activity is called National Income. There are three different ways of measuring this income. First let's remind ourselves of the circular flow.

Figure 1 Circular flow of income

We can measure national income in three different ways. We could look at the total level of expenditure on goods and services being produced by firms. This would include consumer expenditure (C), investment expenditure (I), government expenditure (G) and net export spending (X-M) i.e. C + I + G + (X-M).

Alternatively, we could look at the total level of income generated. This would include all factor incomes - wages, profit, rent and interest. A final possibility is to measure the total level of output produced by firms.

All three of these are methods of calculating national income:

- Total expenditure

- Total income and

- Total output

Each should give the same result, because each is measuring essentially the same thing; i.e. a flow of income over a period of time. The logic of this is that, for the economy as a whole, the value of all output equals what is spent on the output, and what is spent on the output becomes income to those who have produced the output. Thus NATIONAL INCOME = NATIONAL OUTPUT = NATIONAL EXPENDITURE.

For an excellent review of the operation of the Circular Flow of Income, watch the video on YouTube by Paj Holden.

Examining the three methods of calculating national income

Theoretically a government can attempt to find out the level of economic activity by trying to measure the total amount of output produced (the output method) or the income generated from producing it (the income method), or the total expenditure on purchasing it (the expenditure method). Governments try to calculate how much output, income, and expenditure takes place within one year.

To get a basic overview of national income accounting, and in particular the three methods used to measure national income, review the following sites:

- Wikipedia - Measures of national income and output

- Tutor 2U - Measuring national income

- Describe the three methods of calculating national income and explain why they should, in theory, produce the same result

- Identify the problems encountered when measuring national income using the three methods.

- Exaplain how these problems are overcome.

To find national income account data relating to these three accounting methods for countries within the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the StatExtracts site is particularly useful.. You can see the site in the web window below, or follow the previous link to open the site in a new web window.

Find the national accounts link by scrolling down the list on the left hand navigational bar and examine the different measures of national income.

However, in practice a number of difficulties arise when trying to ascribe an accurate monetary value to income, output and expenditure. These difficulties include:

- The unofficial, shadow or informal economy - in which the output is not declared. This is because some producers do not want to pay tax or may be involved in illegal operations. If we look at the expenditure and income methods of measuring national income, we can get some idea of how much undeclared work might be happening. Some of us will be spending income we have not declared! Whatever the scale of this shadow economy, it means that a part of the GDP is understated. The size of the unofficial economy will vary from country to country.

-

Non-marketed goods and services - some transactions do not involve money changing hands. For example, people undertaking voluntary work or helping decorate a friend's house does not appear as earned income, but it can be argued to be part of the production of the economy. Similarly, in less developed countries, much economic activity is part of the subsistence economy in which people grow/make things for themselves and the goods are not sold for money in markets. It has been argued passionately by some that women who stay at home to look after children should have this service valued and included in national income.

Non-marketed goods and services - some transactions do not involve money changing hands. For example, people undertaking voluntary work or helping decorate a friend's house does not appear as earned income, but it can be argued to be part of the production of the economy. Similarly, in less developed countries, much economic activity is part of the subsistence economy in which people grow/make things for themselves and the goods are not sold for money in markets. It has been argued passionately by some that women who stay at home to look after children should have this service valued and included in national income. - Government spending - in the expenditure method of calculating national expenditure, government spending on goods and services is included. However, some government expenditure goes to producing public goods, for example defence, which are not sold. So there is a problem in ascribing an appropriate value to these goods for national income calculation.

What is GDP? (video)

For a basic introduction to GDP watch the video below - What is GDP? (You can do this in the web window below or follow the previous link to open the page in a new web window)

Different national income measures

Gross National Product (GNP) and Net National Product (NNP) - gross and net measures

Just as the national assets (the capital stock) work towards creating new wealth, so some of them wear out and need to be replaced (this wearing out is called depreciation). Unless worn out capital is replaced, the national capital stock shrinks and negative economic growth could be recorded. To stop this from happening, part of national income each year must be invested to repair, replace and make good that part of the capital stock, which ceases to be adequate for use.

When we mention Gross National Product (GNP), we are referring to national income BEFORE the amount needed to replace capital has been deducted. This amount is called capital consumption (or depreciation) and, once this has been deducted, we call the figure Net National Product (NNP).

Net National Product

Net National Product is calculated using the following formula:

NNP = GNP minus capital consumption

Increasingly gross national product (GNP) is being referred to a gross national income (GNI). So remember if you are given GNI data it is the same at GNP!

Gross Domestic product (GDP) and Gross National Product (GNP) - national and domestic

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is similar to Gross National Product (GNP/GNI), but it only measures the flow of output produced within the country. GNP/GNI adds in property income flowing to domestic economic agents from their investments outside the country. It also includes a deduction of those sums that flow out of the country. Property income is income derived from the ownership of assets in the form of profits, interest and rent.

Net National Product

Gross National Product is calculated using the following formula:

GNP/GNI = GDP + net property from abroad (or minus net property income paid abroad)

Although this may appear to be a rather dry, inconsequential topic, the question of property income flows is often of life and death significance for millions of people in the developing countries. While net property income is often positive for developed countries, the figure will inevitably be negative for many of the poorest countries of the world. This reflects their indebtedness to the financial institutions and governments of the industrialised countries and manifests itself in the form of large outflows of interest repayments. It often also reflects the domination of less developed countries by multinational corporations who repatriate profits made from these countries to their centre of operations, inevitably somewhere in the richer part of the world. The impact on living standards of the peoples of these countries is dramatic. These issues are discussed in more detail in section 4.5

Real v money data

One of the most crucial things to look at whenever you look at growth and GDP figures is whether they are in real terms.

Real terms

If a variable is in real terms this means that the effects of inflation have been removed.

If they are not in real terms, then they are described as being in nominal or money terms. This means that they are valued at the same value as money was worth at the time the data was recorded.

However, just to muddle things, the data may not be described as being in real terms. The expression that is often used is that the data is at constant prices. This means that the whole series is expressed at the prices that were ruling in a particular year, e.g. at 2008 prices. If the data is expressed in nominal or money terms, then it may be described as being valued at current prices. So, remember:

Current prices - includes the impact of inflation, as output is valued at prices currently prevailing in markets.

Constant prices - the effect of inflation has been removed and the variable is in real terms.

GDP at constant and current prices - Italy

GDP at constant and current prices - Turkey

The brown line shows GDP at current prices, and this clearly grows a lot faster than GDP at constant prices. The difference between the two datasets is simply inflation. In this graph, GDP is expressed at the prices ruling in the base year of the index.

So, first thing when you look at a piece of data - is it in real or nominal terms?

Current and constant prices

The GDP deflator is a broader index of price increases than the consumer price index. It includes the prices of capital goods as well as consumer goods. It can be used to calculate real changes in the level of GDP. We say that it is used to convert GDP at current prices to GDP at constant prices.

The following table show the GDP deflator indices for two countries, Italy and Turkey

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 100.00 | 102.96 | 106.32 | 109.63 | 112.52 | 114.84 | 116.95 | 119.96 | 123.26 | 125.91 |

| Turkey | 230.07 | 351.67 | 483.28 | 595.74 | 669.62 | 717.05 | 783.96 | 832.73 | 932.61 | 980.65 |

The formula for the GDP deflator is as follows:

![]()

Hence to calculate Real GDP the formula can be rearranged as follows

![]()

Task

- Calculate the increase in the overall level of price increases between 2000 and 2009 for both countries. This will give you a clue why nominal GDP has increased over the period.

- The table below shows the GDP figure at current prices in US $.

| Country Name | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 1,097,344,131,196 | 1,117,358,481,432 | 1,218,921,247,883 | 1,507,171,243,792 | 1,727,825,472,922 | 1,777,693,953,639 | 1,863,380,936,371 | 2,116,201,719,593 | 2,296,628,950,818 | 2,112,780,152,061 | .. |

| Turkey | 266,567,531,990 | 196,005,288,838 | 232,534,560,775 | 303,005,302,818 | 392,166,274,991 | 482,979,839,238 | 530,900,094,505 | 647,155,131,629 | 730,337,495,198 | 614,603,094,839 | .. |

- For the above nominal GDP data calculate the real GDP and add it to a spreadsheet

- Plot the GDP at current prices (nominal) and the GDP at constant prices (real) for both countries between 2000 and 2009. Time should be plotted along the X axis.

- Are there any differences between the two graphs for each country?

- What accounts for the difference between the two sets of data?

Using index numbers

Much of the data you will come across in your course is presented in the form of index numbers and index series. Let's review how index numbers work.

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 89 | 91 | 93 | 96 | 98 | 100 | 102 | 104 | 107 | 108 |

| Turkey | 29 | 45 | 66 | 82 | 91 | 100 | 111 | 120 | 133 | 141 |

The following shows the consumer price index for two countries, Italy and Turkey. The consumer price index is a number calculated every year, which indicates how much on average consumer prices have risen since the previous year.

If we look at prices in Italy between 2000 and 2001 we can see that the consumer price index has increased from 89 to 91. The first point to note is that this DOES NOT MEAN that prices have gone up by 2%. That is not how index numbers work!

To calculate the increase in consumer prices we would need to find the percentage change between these two index numbers.

![]()

In the above example

![]()

We can say, therefore, that the prices have gone up by 2.3% over the two years.

Now it's your turn

Calculate the increase in consumer prices:

- from 2003 and 2007 for both countries

- from 2001 to 2009 for both countries

- from 2008 to 2009 for both countries

NB The index number in 2005 for both countries is 100. This means that the index has been calculated in such a way that all prices are being compared with those that existed in 2005. 2005 is referred to as the base year. Therefore, when you use an index, it is said that you are valuing something in terms of constant prices i.e. in the case of the example, all prices are benchmarked against those that existed in 2005.

Total and per capita

So far we have been talking about national income as the total amount of income earned by the economy and this is an important measure. However, if we want to compare national income between countries, we need to adjust the measure.

So far we have been talking about national income as the total amount of income earned by the economy and this is an important measure. However, if we want to compare national income between countries, we need to adjust the measure.

For example, we would expect the USA to have a higher national income than France, for example, as they have approximately five times the population and more people means the USA should be able to produce more goods and servies. However, what is more important is whether, on average, each person in the USA produces more in value more than each person in France. To calculate this figure, we divide the national income by the population to get 'national income per person' or 'per capita'. Using this measure we are in a better position to compare standards of living between countries. However, when using national income per capita to make international comparisons of welfare, there are still a number of additional factors that need to be taken into account.

Case study - rapid economic growth

China's development could be advanced considerably if the government and the people abandoned their unhealthy fixation on the rise of gross domestic product.

China's development could be advanced considerably if the government and the people abandoned their unhealthy fixation on the rise of gross domestic product.

A recent edition of The South China Morning Post carried a feature expressing the point in a particularly enlightening fashion.

What's so great about rapid economic growth anyway?

For the princely sum of 14,500 yuan (HK$16,800), the magazine's Beijing correspondent joined 30 or so mainlanders for a gruelling 10day, five-country coach tour of Europe.

Watching cultures collide - even at second hand - is always illuminating. No doubt the speed at which the tourists swept past the architectural and artistic glories of Paris, pausing only to snap the obligatory photographic record of their presence before heading off for an orgy of handbag shopping, would have raised some supercilious French eyebrows.

But equally, for their part the visitors were taken aback by the leisurely pace of life in Europe, where the locals linger over coffee, prohibit bus drivers from working more than 12 hours a day, and even stop their cars for pedestrians.

"With a pace like that, how can their economies keep growing?" the Chinese guide asks. "Only when you have diligent, hardworking people will the nation's economy grow."

It's a theme that recurred constantly as the group tore around Europe, with the visitors marvelling at the willingness of French workers to go on strike, and at how many years the Italians take to build a new highway. "If this were China, it would be done in six months," one says. "That's the only way to keep the economy growing."

What's remarkable here is not that the Chinese tourists found Europe slow-moving - Americans have been saying the same for decades - but that their automatic assumption that fast growth is the best, indeed the only, measure of a country's economic success.

This begs the question: what's so great about rapid growth anyway?

That might sound like a dumb thing to ask, but the more you think about it, the more the question makes sense.

The growth our tourists were talking about was in gross domestic product (GDP), which measures the final value of all goods and services produced by an economy.

GDP was developed in the US during the Great Depression, and came into its own during the second world-war as a measure of how many guns, ships and planes the US economy was able to produce. It has been the standard measure of economic strength ever since.

But GDP measures quantity, not quality. In other words, although it says a great deal about how much stuff you can churn out, it tells you very little about the state of your economic development.

For example, GDP counts all investment as positive, whether or not that investment turns out to be productive in the longer run.

So if a country pours resources into building pyramids, its GDP will rise sharply while they are under construction. But considering that pyramids, once complete, add nothing to the economy (except maybe generating tourist revenues four millennia later), it is difficult to claim that their construction furthers economic progress.

This consideration is especially important for China. Although the country's leaders aren't building pyramids, they may be doing the modern equivalent: building hundreds of expensive airports, high-speed rail lines and glittering financial centres that can never hope to generate a return on the investment involved. These projects add to GDP growth in the short term but do nothing to advance economic development.

Similarly, GDP fails to account for the costs of environmental damage. All production is regarded as positive, even if the pollution it causes reduces the productive capacity of the agricultural sector and pushes up health care costs.

Again, this is important for China. A few years ago, the State Environmental Protection Administration did try to factor pollution costs into the country's GDP figures. But when it found that including environmental costs would have reduced growth by at least a third, the attempt was quickly discontinued. That shouldn't have been too surprising given that maintaining high headline GDP growth has become an obsession with China's leaders, who tout rapid growth as the justification for their authoritarian rule.

And as our travellers' comments show, their message resonates strongly with China's people, or at least those rich enough to take package tours round Europe.

But unfortunately the GDP measure by which both China's government and its travelling classes set such store is a deeply flawed measure of true economic progress.

As Simon Kuznets, the US economist who originally developed the idea of gross domestic product, warned: "Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between its costs and return, and between the short and the long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what, and for what."

It's a message China and its leaders would do well to heed.

That's not to say China should immediately embrace a European lifestyle - heaven forbid - but it does mean that the country's economic development could be advanced considerably if only its government and people were to abandon their unhealthy fixation on the rapid growth of GDP.

South China Morning Post (25 May 2011) by Tom Holland (reproduced here with permission of the author)

If you would prefer a pdf version of the original article, please follow the link below:

- Summarize the arguments for slowing down the rapid growth of GDP?

- To what extent do you agree with these arguments?

- Explain the counter arguments in favour of increasing the level of a country's GDP.

Using national income data

It is recommended that you review section 4.2 which looks at the problems of measuring development. Living standards and welfare are considered to be key concepts in economic development. In the previous section we noted that using national income data to measure living standards, and to measure how these change over time, is fraught with potential hazards. Similarly, using national income data to compare the living standards in different countries can also be problematic. In particular, governments have problems:

It is recommended that you review section 4.2 which looks at the problems of measuring development. Living standards and welfare are considered to be key concepts in economic development. In the previous section we noted that using national income data to measure living standards, and to measure how these change over time, is fraught with potential hazards. Similarly, using national income data to compare the living standards in different countries can also be problematic. In particular, governments have problems:

- measuringliving standards of the population

- measuring how living standards change over time

- comparing international living standards

Can you remember the issues associated with using national income data such as GDP to measure living standards?

- The unofficial, shadow or informal economy - in which the output is not declared.

- Non-marketed goods and services - some transactions do not involve money changing hands.

- Government spending -some government expenditure goes to producing public goods, for example defense, which are not sold.

Can you remember the issues associated with using national income data such as GDP to measure how living standards change over time?

- Population numbers change

- income flows to and from abroad change

- Prices change

- It does not take account how income is distributed

When comparing GDP figures between countries, think about the following (Section 4.2 explores many of these issues in more detail):

- How the GDP is distributed

- The type of economy under consideration, e.g. developed or developing

- The costs of basic commodities in certain economies, e.g. housing in UK against an African country

- How taxes are charged and who actually pays them

- What level of social benefits are paid and to whom

- Life expectancy, protein intake and years in education

- Access to basic amenities, such as clean water

- The proportion of goods and services that are not traded, e.g. home-grown food, bartered services. The presence of these can distort national income figures significantly as they will not appear.

- The problem of comparing national incomes expressed in different currencies and the use of the exchange rate for this purpose.

- The composition of the output, e.g. in terms of armaments and welfare services.

- The extent to which additional output has generated negative externalities which may affect the quality of life.

Purchasing power of GDP

Allowances for differences in purchasing power when comparing welfare between countries

We saw in the previous section, that GDP alone is not a completely adequate measure of the standard of living, though it is often used as a proxy for it. If we do use GDP as a measure of standard of living, then we also need to take account of differences between the purchasing power of GDP. If you have travelled, you will be aware that prices of goods in other countries often appear cheaper / more expensive. This may appear the case to us, but not to the people living there.

We saw in the previous section, that GDP alone is not a completely adequate measure of the standard of living, though it is often used as a proxy for it. If we do use GDP as a measure of standard of living, then we also need to take account of differences between the purchasing power of GDP. If you have travelled, you will be aware that prices of goods in other countries often appear cheaper / more expensive. This may appear the case to us, but not to the people living there.

It may be that a lower GDP per capita nevertheless gives the same standard of living, because the same level of income can buy more in a particular country. When comparing GDP between countries, we need to try to adjust for the purchasing power of the GDP. Differences in purchasing power often relate to exchange rate differentials. Although purchasing power is one factor affecting exchange rates, there are many others as well if a country's exchange rate is out of line with what is called the purchasing power parity exchange rate.

When comparing GDP levels between countries, we should try to compare GDP per capita translated at purchasing power parity rates.

Task

- Visit the World Bank data site and find the most recent GDP per capita for the following countries:

- Australia

- US

- Japan

- Thailand

- Italy

- India

- Uganda

- Search the web to identify factors causing the differences between the GDP per capita figures you have found. Present evidence to support your findings.

Alternative measures of GDP

We have seen already that GDP is a rather narrow measure of living standards. There are alternative measures of living standards, such as the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). This index includes development indicators, such as life expectancy and access to education, as well as GDP. In addition, there are a number of single and composite indicators we can use as measures of development. These are explored in more detail in Section 4.2

We have seen already that GDP is a rather narrow measure of living standards. There are alternative measures of living standards, such as the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). This index includes development indicators, such as life expectancy and access to education, as well as GDP. In addition, there are a number of single and composite indicators we can use as measures of development. These are explored in more detail in Section 4.2

The Green GDP

national income statistics provide a rather limited measure of living standards and wellbeing and do not take environmental concerns, such as the depletion of natural resources, into account. In response to this omission, the United Nations and the World Bank introduced the idea of Green GDP. In essence, 'Green GDP' highlights both the contribution of natural resources to economic development and the costs caused by pollution or resources degradation. By including both the use and depletion of natural resources in economic growth, this measure tells us more about the quality of the growth in terms of sustainable development.

Green GDP = GDP -Depletion of Natural Resources - Cost of Pollution

Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW)

Another measure of development is the ISEW This provides a fuller picture of economic welfare because, like the MEW, this index adjusts the GDP figure to allow for actors ignored by GDP. These include:

- Environmental costs - pollution and other environmental costs will be negative figures and therefore reduce economic welfare.

- Defensive expenditures - increased air pollution has in many countries led to greater lung diseases, like asthma. This requires greater government spending, but cannot be said to be positive, so the ISEW adjusts for this.

- Inequality - the greater the level of inequality in an economy, the more the figure for consumption will be reduced. The ISEW adjusts for this inequality.

- Household production - family members who care for elderly relatives or dependents do not get paid for their 'work'. However, their contribution to society is significant. If they did not care, then the bill would be picked up by government or charity, and so their contribution is added back into the ISEW.

- Resource depletion - where resources are used up, this will reduce economic welfare and so, like environmental costs, the ISEW counts this as a negative, whereas GDP counts it as part of economic growth.

After these adjustments are made, we get the ISEW figure which will be a better representation of economic welfare than GDP alone.

While GDP provides a somewhat limited measure of economic growth and living standards, it does have the advantage of being fairly easily obtained and is based on three variables only - income, expenditure and output. In contrast to this, as can be seen from the HDI, MEW and ISEW, development is a multi-dimensional, complex process which can only be judged against a variety of criteria, using composite indices. This may give rise to various problems involving subjective, value judgements on behalf of the statisticians who construct the indices. For example, how should factors such as life expectancy and literacy be weighted within an index? Which factors should be included and which should be excluded? While the HDI, for example, may provide a fairly sophisticated indicator of living standards, it omits some very important components, such as environmental quality; but to construct a development index, which is all-embracing, would be a statistically awesome task!

Case Study

Grossly distorted picture

Read the article Grossly distorted picture. You can do this in the web window below, or follow the previous link to open the article in a new web window.

Having read this article organize a debate about the meaning of quality of life or standard of living. You will need to think through how to word the motion. It should be somewhat contentious to give those debating something to get their teeth into. For example it could be:

"This house believes that the chief aim of a thriving economy is to raise the material living standards of its citizens."

Short term fluctuations and long term trends

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Business cycle

The business cycle, also often known as the trade cycle, is the tendency of economies to move, over time, through periods of boom and slump. In other words, the business cycle represents the fluctuations in the rate of economic growth that take place in the economy.

What the data says (1)

- Visit the World Bank Data site and examine GDP data for your own country over the last 20 years. Using this data, identify the years when the economy was in periods of boom, recession, slump and recovery.

- Explain why governments might want to predict where a country is in its business cycle?.

What the data says (2)

- Import the GDP data for your own country and three others from different continents into a spreadsheet and plot the data. Using this date, comment on whether it is possible to determine a longer term trend in economic activity. If it is possible, construct a trend line to show whether the economy is growing or declining over the longer term.

- Discuss whether the long term trends for all four countries are broadly the same or, whether there differences.

The business cycle in history

The following article explores the business cycle in the UK over the last 300 years. As you read the article, reflect on whether the business cycle has changed over the centuries and consider factors that may underpin cyclical activity in the UK.

The business cycle is explored in more detail in sections 2.2 and 2.4. Specifically, we try to understand what causes the cycle, once it has started, to continue or to change direction.

2.1 The level of overall economic activity (questions)

In this section are a series of questions on the topic - the level of overall economic activity. The questions may include various types of questions. For example:

- Short-answer questions - a series of short-answer questions to help you check your understanding of the topic

- Case studies - questions based around a variety of information

- Long answer - questions requiring an extended/essay type response

- Data response - responding to data or topical economics news articles

Click on the right arrow at the top or bottom of the page to work through the questions.

Self-test questions

1 |

Trade cycleIn which phase of the trade cycle is inflation most likely to emerge? |

2 |

Trade cycleWhich of the following is not a phase of the trade cycle? |

3 |

Trade cycleIn which phase of the business cycle is unemployment most likely to rise? |

Short questions

Question 1

Distinguish between saving and investment.

Question 2

"Saving is a leakage from, and investment is an injection into, the circular flow of income." Identify:

(a) two further examples of a leakage

(b) two further examples of an injection

Question 3

Using a three sector open circular flow of income model:

(a) Explain what is meant by equilibrium

(b) Describe the conditions for the circular flow of income to be in equilibrium

Question 4

Explain what you would expect to happen to the size of the circular income flow if there was an increase in the amount of government spending into the flow.

Question 5

Explain why GDP may not always be the best measure of economic welfare.

Question 6

Analyse two possible factors that will lead to GDP understating the level of economic welfare.

Question 7

Analyse two possible factors that will lead to GDP overstating the level of economic welfare.

Question 8

Explain the main problems with using GDP as a measure of economic welfare.

Question 9

Evaluate two measures of economic welfare and compare these to GDP.

Data response (1)

Read the article Sarkozy seeks le feel-good factor (you can do this in the web window below or follow the previous link to open the article in a new web window) and then answer the questions below.

Question 1

Define Gross Domestic Product.

Question 2

Examine the view that GDP is a useful indicator of living standards.

Question 3

Identify, and evaluate, alternative measures to GDP as indicators of the quality of life of a country.

Question 4

Examine the problems associated with using indicators of living standards, such as GDP across national boundaries.

Data response (2)

Read the following article written by a Ugandan coffee farmer:

And then answer the questions below.

Question 1

Define the term 'buffer stocks.

Question 2

To what extent is Gross Domestic Product is an effective measure of the standard of living on Ugandans.

Question 3

Explain whether an annual growth rate of 5.1% in 2010 means that Ugandans livings standards have increased by an equivalent amount.

Question 4

Disuss the reasons behind the fluctuations in the Gross Domestic Product of Uganda.

Long Questions

Question 1

(a) Explain what is meant by the circular flow of income.

(b) Using diagrams to illustrate your answers, explain the conditions necessary for the circular flow of income of a country to be in equilibrium.

Question 2

(a) Describe the methods by which Gross Domestic Product can be measured.

(b) To what extent can Gross Domestic Product be used as a reliable indicator of living standards, both nationally and internationally?

Section 2.2 Aggregate demand and supply (notes)

In the previous section we considered the level of overall economic activity.

In this section, we examine the concepts of aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Distinguish between the microeconomic concept of demand for a product and the macroeconomic concept of aggregate demand.

- Construct an aggregate demand curve.

- Explain why the AD curve has a negative slope.

- Describe consumption, investment, government spending and net exports as the components of aggregate demand.

- Explain how the AD curve can be shifted by changes in consumption due to factors including changes in consumer confidence, interest rates, wealth, personal income taxes (and hence disposable income) and level of household indebtedness.

- Explain how the AD curve can be shifted by changes in investment due to factors including interest rates, business confidence, technology, business taxes and the level of corporate indebtedness.

- Explain how the AD curve can be shifted by changes in government spending due to factors including political and economic priorities.

- Explain how the AD curve can be shifted by changes in net exports due to factors including the income of trading partners, exchange rates and changes in the level of protectionism.

- Describe the term aggregate supply.

- Explain, using a diagram, why the short-run aggregate supply curve (SRAS curve) is upward sloping.

- Explain, using a diagram, how the AS curve in the short run (SRAS) can shift due to factors including changes in resource prices, changes in business taxes and subsidies and supply shocks.

- Explain, using a diagram, that the monetarist/new classical model of the long-run aggregate supply curve (LRAS) is vertical at the level of potential output (full employment output) because aggregate supply in the long run is independent of the price level.

- Explain, using a diagram, that the Keynesian model of the aggregate supply curve has three sections because of "wage/price" downward inflexibility and different levels of spare capacity in the economy.

- Explain, using the two models above, how factors leading to changes in the quantity and/or quality of factors of production (including improvements in efficiency, new technology, reductions in unemployment, and institutional changes) can shift the aggregate supply curve over the long term.

- Explain, using a diagram, the determination of short-run equilibrium, using the SRAS curve.

- Examine, using diagrams, the impacts of changes in short-run equilibrium.

- Explain, using a diagram, the determination of long-run equilibrium, indicating that long-run equilibrium occurs at the full employment level of output.

- Explain why, in the monetarist/new classical approach, while there may be short-term fluctuations in output, the economy will always return to the full employment level of output in the long run.

- Examine, using diagrams, the impacts of changes in the long-run equilibrium.

- Explain, using the Keynesian AD/AS diagram, that the economy may be in equilibrium at any level of real output where AD intersects AS.

- Explain, using a diagram, that if the economy is in equilibrium at a level of real output below the full employment level of output, then there is a deflationary (recessionary) gap.

- Discuss why, in contrast to the monetarist/new classical model, the economy can remain stuck in a deflationary (recessionary) gap in the Keynesian model.

- Explain, using a diagram, that if AD increases in the vertical section of the AS curve, then there is an inflationary gap.

- Discuss why, in contrast to the monetarist/new classical model, increases in aggregate demand in the Keynesian AD/AS model need not be inflationary, unless the economy is operating close to, or at, the level of full employment.

- Explain, with reference to the concepts of leakages (withdrawals) and injections, the nature and importance of the Keynesian multiplier.

- Calculate the multiplier using formulae.

- Use the multiplier to calculate the effect on GDP of a change in an injection in investment, government spending or exports.

- Draw a Keynesian AD/AS diagram to show the impact of the multiplier.

Aggregate demand and supply - introduction

In this section we consider the following topics in detail:

In this section we consider the following topics in detail:

- Aggregate demand

- Aggregate supply

- Equilibrium

- The Keynesian multiplier

As economists we want to be able to model what is happening in an economy - particularly in the macroeconomy. This enables us to analyse what causes changes in the economy at the macro level and to develop appropriate policies to achieve our macro goals.

In managing a country's economy, governments are usually aiming to:

- Maintain high levels of employment or full employment

- Maintain price stability - low and consistent levels of inflation

- Maintain a satisfactory balance of payments

- Maintain high levels of economic growth

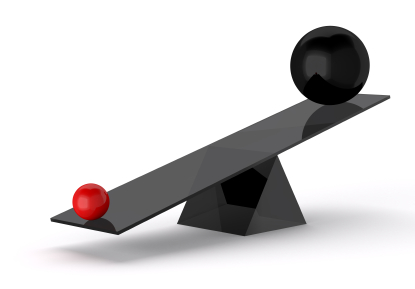

There will always be trade-offs between these macroeconomic goals, because it can be difficult to maintain all of them at once; governments will, as a result, face decisions on acceptable levels for each target.

In trying to understand the various macroeconomic problems a country might face, and the policies that its government may adopt in response, it is useful to look at one of the most common theoretical frameworks for analysing the macroeconomy; those of aggregate demand and supply. These are similar to the concepts of demand and supply that we considered in Section 1, but with the addition of the word 'aggregate'. Agregate means 'the sum of', so we are now looking at total demand and supply in the whole economy, instead of demand and supply of goods and services in individual markets.

The AD/AS model

The AD/AS model is central to macro-economic analysis, because it focuses on the determination of the equilibrium level of real output and the level of prices.

Using AD and AS curves, allows us in a relatively simple way, to illustrate complex inter-relationships and linkages, that are characteristic of market economies.

Why is the AS/AD model important for exam success?

It is relevant across a wide area of macro-economics and allows you to tackle a variety of macro-economic questions using a formalised mode of analysis, rather than relying purely on descriptive or ad hoc approaches. It is, therefore, an excellent tool for accumulating marks in HL and SL economics exams.

What are the differences between the AD/AS model and the D&S model?

Figure 1 Demand and supply and AD/AS compared

Aggregate demand curve

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Changes in aggregate demand

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

N.B. A change in the price level will simply be represented by a movement along the AD curve.

Short-run aggregate supply (SRAS)

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Changes in SRAS

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Long run aggregate supply (LRAS) - classical

The neo-classical approach

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Changes in LRAS - classical

The neo-classical approach

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Long run aggregate supply (LRAS) - Keynesian

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Aggregate supply changes

Many economists argue that the LRAS curve is vertical, which means that any increase in AD will lead to an increase in prices. They feel that a time lag exists between the level of demand increasing and the supply sector of the economy being able to expand to meet this. They argue that only through increases in LRAS will such rises in AD be met without inflationary pressures.

Supply-side policies may enable the economy to expand in a non-inflationary way, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Impact of supply-side policies

Full employment level of national income

As we have seen in previous sections, national income can be calculated by measuring the total level of output of the economy. Generally speaking, the more the economy produces, the more people will be needed to produce the goods and services. However, there will be a maximum level of output where everyone available is employed and no more output can be produced. This level of output is called the full employment level of national income. At this level of income, everyone who wants a job will have a job and there is no shortage of demand in the economy.

We can see the level of full employment income in Figure 1 below - Yfe.

Figure 1 Full employment national income (Yfe) - Keynesian and Neo-classical

In practice, there may still be some unemployment at this level of income, but this would be caused by institutional factors like the level of social security payments or perhaps seasonal factors. However, at the full employment national income the economy is producing as much as it is able to in current circumstances.

Equilibrium national income

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

The essentials of AD and AS

As is said in their titles, both aggregate demand and supply curves are aggregates - that is, they are the total of either all demand or supply within the economy. Aggregate demand slopes downwards as any other demand curve and shows that as the aggregate demand for real output increases, the average price level in the economy falls. This is the same relationship you studied when looking at individual demand. As with effective demand for individual products, a change in any of its components will SHIFT the AD curve to a new position. So, if a country becomes more successful in exporting its products to other countries, the AD line will shift to the right as in the diagram below (Figure 2). A similar situation will arise if the government stimulated the economy via expansionary fiscal or monetary policy.

Figure 2 Increased aggregate demand

The aggregate supply curve shows the total output of goods and services, which the firms or producers or suppliers will, or plan to supply, at a given price level. As we saw previously, a change in any of the determinants of AS, apart from the price level, will shift the AS curve to a new position.

If, or when, any of these change the curve can shift. In the diagram below (Figure 3), import prices have fallen and so too have the costs of production - the AS curve has therefore moved to the right (outwards).

Figure 3 Increased aggregate supply

Have a go at shifting the AD/AS curves for each of the changes below, draw original equilibrium AD and AS curves and show how the equilibrium has changed. Once you have answers to the outlined changes, follow the links to see if your answers agree with ours.

Illustrate the effect on equilibrium of the following:

- The central bank is concerned about future inflation and so increases interest rates.

- The exchange rate depreciates, leading to a fall in export prices and an increase in import prices.

- Consumers are concerned about high levels of debt and so reduce spending and increase saving to try to reduce their indebtedness.

Answer 1

Answer 2

Answer 3

Changes in short-run equilibrium - summary

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Equilibrium in the long run?

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Non-inflationary growth

LRAS can be shifted through supply-side policies, and free market economists argue that, if these are used, the economy can grow in a non-inflationary way as in Figure 1 below. We will look at these policies in more detail in the next section.

Figure 1 Impact of supply-side policies

It is generally accepted that there is a relationship between output and employment and, that as output increases, so employment will rise. This seems easier to prove in the short term than it is in the long term. For example, if we make a major breakthrough in technology then output will certainly increase, but will it lead to a similar reaction in employment?

Equilibrium in the Keynesian model

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Inflationary and deflationary gaps

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Any fluctuations in growth must be caused either by changes on the demand-side or changes on the supply-side of the economy. So what can cause these demand-side or supply-side changes?

1. Demand-side shocks

These might be caused by a variety of different events, but they all cause demand to change more suddenly than had been expected. A downturn is normally the more difficult to deal with, although excessive growth may result in inflationary pressures. Such shocks might have resulted from a previous bout of inflation, or a subsequent rise in unemployment or any event that reduces consumer confidence and causes demand to fall. An example is the impact of the swine flu in a country. A demand-side shock is illustrated by shifting AD left.

2. Supply-side shocks

Supply-side shocks can be just as devastating, though, as their name suggests, they are the result of something happening on the other side of the economic equation. It could be a war, drought, natural catastrophe or anything that causes the supply chain to be adversely affected. A supply-side shock is illustrated by shifting AS left.

Remember business and economic planners like stability and certainty, so any 'surprise' event can cause calculations and confidence to be blown off course.

Other possible causes of a cyclical pattern of growth could be:

- Policy-induced changes - politicians have often been known to put in place policies to boost the economy. It would be cynical to suggest that this often occurs around election time, but it does. This can lead to booms which lead to the incoming government having to deflate to slow the economy down again. There is much evidence to suggest the existence of an electoral cycle.

- Imported cycles - if the rest of the world is growing in cycles, then this will affect particular countries. Exports may fluctuate, which means that aggregate demand will change and therefore growth changes

- Expectations - expectations can have a powerful effect on growth. For example if firms expect there to be a slowdown, they may delay investment plans. If they do that, then aggregate demand will fall. If aggregate demand falls, so does growth.

Keynes vs. Hayek (video)

For a slightly different summary of the arguments between the Keynesian and Neo Classical economists why not watch and listen to the video clip. It presents a hip hop song imagining a debate between John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek. Try to follow the argument.

The Keynesian multiplier

Multiplier

The multiplier refers to the phenomenon, whereby a change in an injection of expenditure (either investment, government expenditure or exports), will lead to a proportionately larger change (or multiple change) in the level of national income i.e. the eventual change in national income will be some multiple of the initial change in spending.

We need to be aware that changes in any of the components of AD (e.g. investment) may have a larger effect on GDP than just the value of the change. This is known as the multiplier effect. Let's look at what may happen if there was an injection of extra money into government-provided health care in an economy. Certainly, some of the money will go to doctors and nurses in the form of a salary increase or to employ new doctors and nurses, but new building and equipment will probably also be bought. This will boost sales of those making such items and so allow them to consume more. This 'first round effect' is the big boost to spending within the economy.

We need to be aware that changes in any of the components of AD (e.g. investment) may have a larger effect on GDP than just the value of the change. This is known as the multiplier effect. Let's look at what may happen if there was an injection of extra money into government-provided health care in an economy. Certainly, some of the money will go to doctors and nurses in the form of a salary increase or to employ new doctors and nurses, but new building and equipment will probably also be bought. This will boost sales of those making such items and so allow them to consume more. This 'first round effect' is the big boost to spending within the economy.

However, doctors eat, drink and consume just like the rest of us, and they will choose to spend some of their additional salary, known as their marginal propensity to consume (MPC) and save the rest, known as their marginal propensity to save (MPS). So, if a doctor was awarded an extra $100 in salary and chose to spend $80 of this, his or her MPC would be 0.8 and his or her MPS would be 0.2. MPC and MPS must add up to 1, since additional money can only be saved or spent.

The producers of the goods and services that the doctor now buy buy will take on more labour to cope with the extra demand and these new employees will also spend part of their additional income and so it goes on. The amount that is passed on will diminish in each successive round of spending but the overall injection into the economy will be greater than the first sum that was put into it. The size of the multiplier can be worked out by dividing the increase in national income that eventually occurs by the increase in injections that caused it.

![]()

So, for example, if an increase in government spending of $10m caused GDP to rise by $50m, this would be a multiplier of 5. This would be found by dividing $50m (the change in GDP) by $5m (the initial change in injection of expenditure).

The key determinants of the value of the multiplier are:

- The size of the savings ratio - the more people save of any increase in income (MPS), the less the increase in spending at each stage of the process.

- The amount spent on imports - if a lot of the extra spending created goes on imported goods and services, then this money will be lost out of the country and not passed on within the economy (the marginal propensity to import or MPM).

- The level of taxation - any increase in income will also mean higher tax revenue. However, if the government use this extra revenue to spend on public sector investment and employment, then this may help the process continue.

Overall, the value of the multiplier therefore depends on the amount of any increase in income that is spent by the people receiving it. The higher the MPC, the higher the value of the multiplier will be.

Marginal propensity to consume (MPC)

The marginal propensity to consume is the proportion of each extra dollar of income spent by households. For example, if a person earns $1 more and consumes 70c of it, then the MPC is 0.7.

The value of the multiplier can be calculated from the following formula:

![]()

Where MPC is marginal propensity to consume and MPS is marginal propensity to save.

But, how exactly is the multiplier determined?

Section 2.2 Aggregate demand and supply (simulations and activities)

In this section are a series of simulations and activities on the topic - aggregate demand and supply. These simulations and activities might include:

- Interactive diagrams - diagrams where you can drag curves or sliders to see the impact of the changes on the diagram

- PlotIT - a chance to build diagrams from data

- Step-by-step - diagrams built up step by step to help you see how to draw them and understand the principles behind the diagram

Click on the right arrow at the top or bottom of the page to move on to the next page.

Diagram toolkit

In the diagram toolkit you get given a panel showing possible curves and labels and you then drag these curves onto targets on the diagram to try to build an appropriate diagram.

There are a number of sections. Follow the links below to access the different sections or use the table of contents on the left.

- National income equilibrium (1)

- National income equilibrium (2)

- National income equilibrium (3)

- National income equilibrium (4)

Why not try the one below as some practice? Drag curves and labels onto the targets on the diagram to build a demand and supply diagram showing a market in equilibrium. Once you think the diagram is right, click 'Check answer'. To see the correct answer, click the 'Feedback' button.

Click on the right arrow to start trying out the diagram toolkit.

National income equilibrium (1)

On the diagrams below, drag curves and labels from the panel on the right to build the appropriate diagram. Once you think the diagram is right, click 'Check answer'. To see the correct answer, click the 'Feedback' button.

Number 1

Number 2

Number 3

Number 4

Click on the right arrow try some further examples.

National income equilibrium (2)

On the diagrams below, drag curves and labels from the panel on the right to build the appropriate diagram. Once you think the diagram is right, click 'Check answer'. To see the correct answer, click the 'Feedback' button.

Number 1

Number 2

Number 3

Number 4

Click on the right arrow try some further examples.

National income equilibrium (3)

On the diagrams below, drag curves and labels from the panel on the right to build the appropriate diagram. Once you think the diagram is right, click 'Check answer'. To see the correct answer, click the 'Feedback' button.

Number 1

Number 2

Number 3

Number 4

Click on the right arrow try some further examples.

National income equilibrium (4)

On the diagrams below, drag curves and labels from the panel on the right to build the appropriate diagram. Once you think the diagram is right, click 'Check answer'. To see the correct answer, click the 'Feedback' button.

Number 1

Number 2

Number 3

Number 4

DragIT - Aggregate demand and supply

The above diagram shows an aggregate demand curve and an aggregate supply curve, with equilibrium real national income (Ye) and the price level (Pe) where the two curves intersect.

First, drag the two lines in turn to show the influence of (a) increased aggregate demand and (b) increased costs on the price level and national income.

Second, click the 'Rotate AS line' button so that the AS curve becomes more elastic and then again drag the two lines in turn and note the effects on Ye and Pe.

Referring to the above diagram, are the following statements true or false? In each case assume that nothing else changes. (Try dragging the lines to check on your answer.)

1 |

Shifts in aggregate supply and demandAn increase in aggregate demand will cause higher inflation. |

2 |

Shifts in aggregate supply and demandAn increase in costs will make the aggregate supply curve more inelastic. |

3 |

Shifts in aggregate supply and demandThe less responsive is AS to a rise in AD, the more prices will rise for a given increase in AD. |

4 |

Shifts in aggregate supply and demandAn increase in expenditure tax will shift both the aggregate demand and supply curves to the left. |

5 |

Shifts in aggregate supply and demandAn improvement in productivity will shift both the aggregate demand and supply curves to the right. |

2.2 Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply (questions)

In this section are a series of questions on the topic - aggregate demand and supply. The questions may include various types of questions. For example: