Depreciation

![]()

Profit is earned at the time that an item is sold. This is when ownership changes from the seller to the buyer, regardless of whether the money has actually changed hands or not.

Profit is rarely held in the form of cash

Capital expenditure goes to the balance sheet, but does not go directly as a cost to the profit and loss account. Look at the following example.

Maze Green Yachts plc

The company buys a new injection-moulding machine for $600,000, which it will use to make parts for its boats for the next 10 years, the estimated life of the machine.

The $600,000 is clearly capital expenditure, so goes to the balance sheet, as does the spending of the cash. This illustrates the principle of double entry and equal and opposite effects. Buying the machine has two consequences. Maze Yachts:

- increases an asset - the injection-moulding machine (fixed assets↑)

- decreases an asset - cash (current assets ↓)

The question is how the cost of the machine should be recorded in the profit and loss account. The cost of the machine should be spread across its useful life, so that a charge is made against profit each year equal to the value of the 'wear and tear' resulting from its use in production. In this case, 10% of its value is added to the costs for each of the next 10 years' profit and loss accounts. Thus an allowance for the purchase of capital items is made using the device known as depreciation.

Depreciation

Depreciation is a non-cash expense (or a non-monetary movement) that reduces the value of an asset as a result of wear and tear, age, or obsolescence. Most assets lose their value over time (in other words, they depreciate), and must be replaced once the end of their useful life is reached. There are several accounting methods that are used in order to write off an asset's cost over the period of its useful life. Depreciation lowers the company's reported earnings, but because it does not involve a cash outflow in the way that other expenses do, so increasing the firm's available cash flow.

Depreciation is effectively subtracted from the balance sheet and added to the profit and loss account as a cost or expense. However, no money actually moves; it is merely an accounting or book entry. Depreciation is an allowance, not a real cost.

Not all fixed assets are depreciated. Over a period of time, property is likely to increase in value or appreciate. Firms deal with this by periodically revaluing these assets in the balance sheet to reflect market or resale value

There are a variety of methods used by firms to calculate the depreciation of fixed assets. However, the two main methods in use are:

- Straight line method

- Reducing balance method

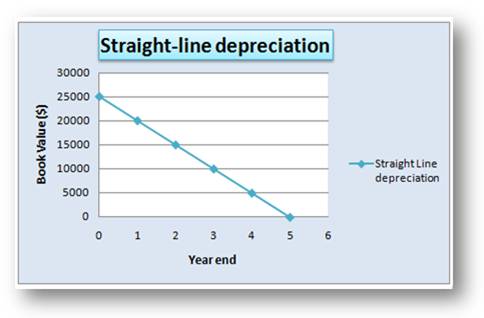

Straight-line depreciation (SLD)

This method, also known as the fixed instalment method, is the most commonly used method of depreciation. It is also the easiest method to understand and calculate.

Once the annual depreciation provision has been calculated, this will remain the same for each year the asset is in use. The formula for calculating the annual rate of depreciation is as follows:

![]()

The scrap value (sometimes known as either residual value or disposal value) will, in most cases be an estimate. It is common, keeping in line with prudence, to have a zero scrap value - due to the uncertainty of any estimate.

Example 1

A delivery vehicle was bought for $25,000. The firm plans to keep it for five years and then trade it in for $3,000 (in effect the trade in value becomes the scrap value).

Example 1 - answer

The depreciation to be charged would be:

![]()

If, after four years, the vehicle had no trade-in value, then the charge for depreciation would have been:

![]()

This amount of depreciation would appear in the profit and loss account as a debit entry (i.e. a charge against the profit) for five years running. The balance sheet value would reduce by the depreciation provision each year for five years. In other words, the balance sheet value of this asset would fall each year by $5,000 for five years running until the assets has no value in the balance sheet - because it has no value to the firm!

Straight-line as a percentage

It is fairly common to express straight-line depreciation as a percentage. This simply means that a percentage of the original cost of the asset will be charged as the depreciation. For example, if an asset cost $10,000 and depreciation is to be calculated at 10% on cost - this would mean that we should charge 10% x $10,000 ($1,000) as the annual depreciation for each year that we have the asset.

The percentage quoted under the straight-line method will also tell us how long we expect the asset to last, for example:

10% - 10 years

25% - 4 years

20% - 5 years

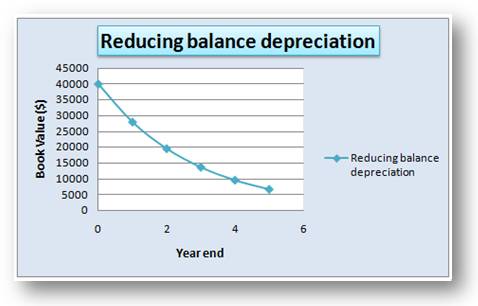

Reducing (declining) balance method

In this method, the annual depreciation is based on a percentage of the asset's net book value (i.e. what the asset is worth in the firm's accounts). The net book value of an asset is calculated as follows:

Net book value = original cost - accumulated depreciation

As the depreciation charged against an asset builds up over time, the net book value of an asset would decrease. Therefore, although the percentage used in this method remains constant, the depreciation charge (in $) will become smaller, the longer we have the asset.

This method is also known as the diminishing or declining balance method.

The percentage rates chosen for reducing balance may seem as if they are chosen randomly, without any real explanation. However, there is a formula, which takes into account the cost, the scrap value, and the expected lifespan of the assets. This formula calculates the percentage that should be used. We do not include it here because it is not a requirement of the course for you to know the formula and it is, without any doubt, one of the most complicated formulae you would ever be likely to see!

With both methods, there may be variations used. Some firms will charge depreciation for each month that the asset is owned. In this case, an asset bought half way through the year would only have half of one year's depreciation charged for it. Some firms may charge a full year's depreciation for any assets, regardless of whether it was owned for the full year. Some firms will not charge depreciation in the year of sale, or in the year of purchase. Each question should tell you which of these rules the firm is applying.

Example 2

Equipment is bought for $40,000 with a residual value of approximately $6500. The depreciation is to be charged at approximately 30% per annum using the reducing balance method.

Example 2 - answer

The calculations for the first three years would be as follows:

| $ | |

|---|---|

| Cost | 40,000 |

| First year depreciation (30% x $40,000) | 12,000 |

| Net book value after first year | 28,000 |

| Second year depreciation (30% of $28,000) | 8,400 |

| Net book value after second year | 19,600 |

| Third year: depreciation (30% x $19,600) | 5,880 |

| Net book value after third year | 13,720 |

| Fourth year depreciation (30% of $13,720) | 4,116 |

| Net book value after fourth year | 9,604 |

| Fifth year: depreciation (30% x $9,604) | 2,881 |

| Net book value after fifth year | 6,723 |

With this method, the depreciation can continually be charged until the asset loses all of its value. If there is a scrap value for the asset as in this example, this method will depreciate the value down to the scrap value rather than to zero. However, as this shows, it is difficult to find the depreciation percentage to achieve the exact scrap value.

Remember, both methods can be quoted using percentages for the depreciation.

- Straight line is a percentage of the cost of the asset

- Reducing balance is a percentage of the net book value of the asset.

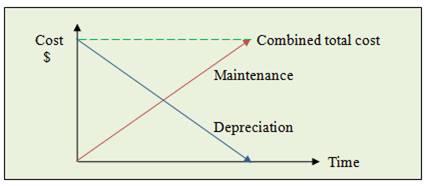

Choice of method

Notice that with the reducing balance method, the depreciation provision per year will start off relatively large and will gradually get smaller. It has been commented that this method of depreciation is superior to the straight-line method, because it is more realistic with asset valuations - assets do lose more of their value in the earlier rather than the later years.

In addition, the total cost of a machine or vehicle is made up not just of the purchase price, but the maintenance costs as well. In the early year when the asset is new, the maintenance costs are low, but the depreciation charge is high. In the later years when the asset is older, the maintenance costs tend to increase, but the depreciation charge falls. So the combined value of depreciation plus maintenance is relatively constant.

However, the counter-argument is that calculating annual amounts for depreciation should not be primarily concerned with providing realistic values for asset values - it is simply an accounting method of 'spreading' the cost of the asset over its useful life.

Example 3

A firm has just bought a machine for $30,000. It will be kept in use for four years, and then it will be disposed of for an estimated amount of $2,000. The question asks for a comparison of the amounts charged as depreciation using both methods.

Straight-line method: ($30,000 - $2,000) / 4 = $7,000 per annum

Reducing balance method: 50 per cent will be used.

See if you can calculate depreciation using both methods and then follow the link below to see how you got on.

Example 3 - answer

This example illustrates the fact that using the reducing balance method has a much higher charge for depreciation in the early years, and lower charges in the later years.

Also when using reducing balance, unless we use a percentage rate with decimal places, we are unlikely to get exactly to the scrap value at the end of the life of the asset

In theory, it does not really matter which method is selected. With both methods, the full costs of the asset will pass through the profit and loss account over its lifespan, although in each individual year different amounts will appear, depending on which method is selected. In practice this may be important to mimise tax liabilities. In addition, some countries require that one of the methods be used.