Topic pack - Operations management - introduction

Welcome to this Triple A Learning topic pack for Operations management. The pack has a wide range of materials including notes, questions, activities and simulations.

A few words about Navigation

So that you can move to the next page in these notes more easily, each page has navigation tools in a bar at the top and the bottom. These tools are shown below.

![]() The right arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the next page of content.

The right arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the next page of content.

![]() The left arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the previous page.

The left arrow at the top or bottom of the page will take you to the previous page.

![]() The home button will take you back to the table of contents for the pack.

The home button will take you back to the table of contents for the pack.

The pack is split into a series of sections and to access each section, the easiest way is to use the table of contents on the left-hand side of the page. To return to the full table of contents, please click on the 'home button' at any stage.

Higher level extension material

Some of the material in this pack relates to the higher level extension topics in the Business and Management guide. This material is marked by icons as follows:

This icon indicates the start of the higher level extension material.

This icon indicates either:

- The higher level extension material continues on the next page or

- The higher level extension material continues from the previous page

This icon indicates the end of the higher level extension material.

Terms and definitions

One of the key things you need to be sure to know, are the definitions of all key business terms. In this section we give you explanations and definitions.

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Click on the right arrow at the top or bottom of the page to start looking at the definitions.

Aims of the business and management course

The aims of the business and management course at HL and SL are to:

- promote the importance of exploring business issues from different cultural perspectives

- encourage a holistic view of the world of business

- enable the student to develop the capacity to think critically about individual and organisational behaviour

- enhance the student's ability to make informed business decisions

- enable the student to appreciate the nature and significance of change in a local, regional and global context

- promote awareness of social, cultural and ethical factors in the actions of organisations and individuals in those organisations

- appreciate the social and ethical responsibilities associated with businesses operating in international markets.

Assessment Objectives

Having followed the business and management course at HL or SL, students will be expected to:

- demonstrate knowledge and understanding of business terminology, concepts, principles and theories

- make business decisions by identifying the issue(s), selecting and interpreting data, applying appropriate tools and techniques, and recommending suitable solutions

- analyse and evaluate business decisions using a variety of sources

- evaluate business strategies and/or practices showing evidence of critical thinking

- apply skills and knowledge learned in the subject to hypothetical and real business situations

- communicate business ideas and information effectively and accurately using appropriate formats and tools.

In addition to the above, students at HL will be expected to:

- synthesize knowledge in order to develop a framework for business decision-making.

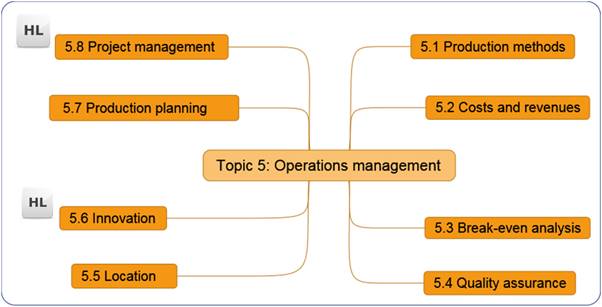

Topic Five Structure

Topic five has six core sub-topics and two HL extension topics.

Operations Management (OM) - Introduction

All businesses produce something, be this tangible or intangible. Traditionally, when we think of production we tend to think of firms manufacturing physical goods in factories and on production lines. However, the experience of most modern, developed economies is that the manufacturing element is actually a smaller part of the economy than the provision of services. There are exceptions; Germany, for example, is still a significant manufacturing and exporting economy.

Production is concerned with converting inputs such as raw materials into finished products which will meet the needs and wants of the market and the customers within them. The process of production will add-value allowing firms to charge a higher price for the finished product than it paid in terms of costs

Production describes a relatively static process, but the term operations management refers to the management of the production process and describes a far wider range of activities; it is far also better suited to firms that produce services rather than physical goods.

What is Operations Management?

Operations Management is concerned with the design of products and services and the management of processes and supply chains. It describes the acquisition, development, and utilisation of the resources that firms require to produce and deliver the goods and services that their customers want.

Operations management covers both strategic and tactical activities. For example, senior management will need to make strategic decisions about the size and location of factories and the levels of research and development as well as planning appropriate supply chains. Middle management and supervisory staff will be more concerned with tactical issues including factory design, layout and structure, project management and equipment selection and replacement. At an operational level, decisions will focus on activities like production scheduling, stock processes and material handling, quality control and maintenance policies.

Operations management is concerned with activities within all three sectors of the economy:

- primary sector, e.g. extracting raw materials and the harvesting of crops

- secondary sector, e.g. manufacturing, construction and processing

- tertiary sector, e.g. service provision.

5.1 Production methods notes

In this section we will examine production methods.

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Describe and compare the features and applications of each method

- Analyse the implications for marketing, human resource management and finance that arise from changing the production system

- Analyse the most appropriate method of production for a given situation

- Understand the needs for organisations to use more than one method of production

Production methods

We start this module on operations management by looking at the methods used by firms to produce. Different products require different production techniques. As you work through this section, try to think what impact these different production methods will have on the other areas of the firm's activities - such as marketing, human resource management and finance. Production is part of an integrated system and cannot be considered in isolation; it will impact on other areas of business as well as being influenced by these.

The production techniques used by industry can be divided into three main categories.

- Job production

- Batch production

- Flow production

We look at each of these on the following pages.

Job production

Job production

Job production is the manufacture of individual 'one-off' or unique items made to customer specifications. The product is seen through the whole process, from start to finish, by an individual or group of workers. The production of the next individual item does not begin until the previous job is complete.

Job production is associated with bespoke production, where each product is made individually and to order; customised to the buyer's specification, such as buildings, paintings, designer clothes, meals and haircuts. Production is a highly skilled process and goods may be handmade and labour intensive. Production costs are usually high, particularly the labour element and, as a consequence, premium prices can be charged.

Job production is associated with bespoke production, where each product is made individually and to order; customised to the buyer's specification, such as buildings, paintings, designer clothes, meals and haircuts. Production is a highly skilled process and goods may be handmade and labour intensive. Production costs are usually high, particularly the labour element and, as a consequence, premium prices can be charged.

Job production covers both small-scale, low technology projects as well as large, complex projects involving high technology. Products are one-off and often unique, such as portraits or tailor made suits, but may be produced singly to a repeated design, such as aircraft, luxury sports cars and yachts.

Job production is well suited to smaller firms as there are few opportunities for economies of scale and the market is less price-sensitive. However, large-scale projects may satisfy the objectives of larger firms in terms of revenues and profit levels; examples of which include major one-off construction projects. At both ends of the scale, job production is appropriate for a business which focuses on meeting customer needs.

The management of job production may be difficult, as the processes differ from job to job. Management of larger products need to place emphasis on cost control and cash flow because payments for products made to order, such as yachts and buildings, may not be made until completion and/or delivery. There may also be penalties for late delivery of large products, so management need to monitor progress (we cover this in more detail in section 5.8 on project management).

For the advantages and disadvantages of each production method, see the advantages and disadvantages summary interaction (page C7).

Batch production

Batch production

Batch production is where the manufacturing process is split into a number of different operations; each of which is carried out on the whole batch before it is moved on and another batch received. The batch is moved on from one stage of production to the next until all the manufacturing processes are completed. Batch production involves the manufacture of a group of identical items and is normally used when the demand for the product is relatively constant.

Batch production involves the production of identical products made in groups (batches). The group remains together as it passes through each stage of production until all processes are complete. Changes may be made between batches. For example, clothing may be produced in batches of different sizes and colours. The process, therefore, includes a delay between batches while equipment is changed or recalibrated; this is known as downtime.

Batch production involves the production of identical products made in groups (batches). The group remains together as it passes through each stage of production until all processes are complete. Changes may be made between batches. For example, clothing may be produced in batches of different sizes and colours. The process, therefore, includes a delay between batches while equipment is changed or recalibrated; this is known as downtime.

Production is less personal in that products are not individualised to customer requirement; the focus is on making high quality products at an affordable price. Workers specialise and are less likely to be highly skilled or multi-skilled. Specialised equipment is probably used since it is possible to get higher capital utilisation. Products are cheaper, but capital cost is significantly higher than for job production.

Typical products produced in batches include bakery products, clothing, 'fast-food', shoes and pharmaceuticals.

For the advantages and disadvantages of each production method, see the advantages and disadvantages summary interaction (page C7).

Flow/mass production

Flow production

Flow production is where all the different operations required for production are carried out in a sequence one after the other. It is usually used where mass production is required to meet high levels of demand and when the product being manufactured is reasonably standardised.

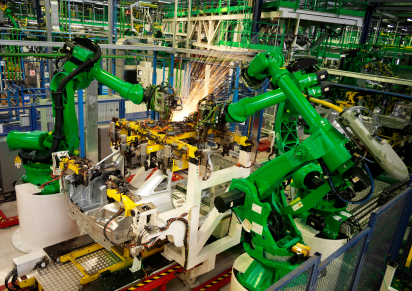

Flow production is the continuous movement of items through each stage of production, often along a conveyor belt or assembly line. Individual jobs are done in sequence. Also known as mass or line production, the process involves the manufacture of a large volume of identical, standardised products. Flow production is highly capital-intensive and has high set-up costs, requiring firms to operate near capacity (high capacity utilisation).

Flow production is the continuous movement of items through each stage of production, often along a conveyor belt or assembly line. Individual jobs are done in sequence. Also known as mass or line production, the process involves the manufacture of a large volume of identical, standardised products. Flow production is highly capital-intensive and has high set-up costs, requiring firms to operate near capacity (high capacity utilisation).

Employees are normally semi-skilled and the process is suited to both mechanisation and automation. The assembly line is often associated with the motor industry, with the Ford 'Model T' being given as one of the first examples of this method of production.

Flow production allows for Economies of Scale and Specialisation (Division of Labour), which are examined in more detail in the Business organisation and environment topic pack. Specialised staff tend to work on a single task, but as we see in the next section, this may not always be the case, especially if a firm employs cell production techniques.

Although standardisation is given as both an advantage and disadvantage of flow production, new technologies have allowed varied products to be designed, developed and produced more rapidly, flexibly and cheaply, often with better quality, e.g. computer assisted design (CAD), computer assisted manufacture (CAM) and automation using robots. More flexible and sophisticated automation of lines has allowed mass produced items to be more customised.

The following video on the Ferrari assembly line illustrates how mass production can be adapted to a more customised product.

For the advantages and disadvantages of each production method, see the advantages and disadvantages summary interaction (page C7).

Halo Custom Guitars

Read the article Halo Custom Guitars Offers Build-to-Order Musical Instruments (you can do this in the window below or follow the previous link to read the article in a separate window) and then consider answers to the questions below.

Question 1

Distinguish between job production and mass production.

Question 2

Explain how automation offers opportunities for increased customisation in the process of mass production.

Question 3

Analyse the advantages and disadvantages of using mass production to produce guitars.

Summary of production methods

Job Production - made to order with specific features e.g. Olympic Stadia.

Batch Production - a group of items passing through a number of stages as a batch, together e.g. bread: dough made, loaves produced, put in oven, sliced, wrapped, or McDonalds burgers.

Mass/Flow Production - an item moves or flows from one stage of a process directly to the next, often by conveyor belt (a continuously moving process) e.g. cars , electronic and 'white goods'.

Task

Have a look at the 'How everyday things are made' web site. This shows you the production process of a wide range of goods. You can look at the site in the window below, or you can follow the previous link to view it in a separate window.

From the web site, find an example of job production, batch production and flow production.

Advantages and disadvantages of production methods

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Continuous production

A variation of flow production is continuous production. Here materials flow continuously through a process, and the product is produced continuously. Good examples are oil refining, the manufacture of detergents and the manufacture and printing of newsprint.

All these production techniques can be summarised as follows:

| Job production | Batch production | Flow production | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Output potential | Low | Intermediate | High |

| Capital requirement | Low | Intermediate | High |

| Product quality | High | Intermediate | Lower |

| Flexibility of product | High | Intermediate | Low |

| Unit cost | High | Intermediate | Low |

| Labour skill requirement | High | Intermediate | Low |

| Labour productivity | Low | Intermediate | High |

Observe the trade-off between productivity and flexibility.

Much work has been done on flow production to increase its flexibility and quality. Computer organisation and control, for example, has revolutionised car assembly

Job production can generally be considered as being labour intensive.

Flow production can generally be considered as being capital intensive.

Cost structure of firms

Some production techniques will be labour intensive and some will be capital intensive. So what do these terms mean?

Labour-intensive

A labour-intensive industry is one where the cost structure is largely made up of variable cost, with labour being the main resource required for production. Job production is a highly labour intensive production method with the cost of labour being significantly higher than the cost of the capital structure, such as machinery. The service sector includes many examples of labour-intensive activities, including schools, banks and legal firms.

Capital-intensive

A capital-intensive industry is one with a high quantity of capital per worker and, therefore, a relatively high proportion of capital costs compared to the cost of labour. Capital-intensive firms require large amounts of fixed assets and/or cash to operate and need a high volume of production and a high margin to provide adequate returns on investment. Capital-intensity is typical of mass and flow production. Steel, automobile manufacturing and mining are examples of capital-intensive industries.

The difference between an activity which is labour-intensive and one that is capital-intensive has significant implications for a firm and there is often a link to the size of the business. Small firms tend to be more labour-intensive than larger ones. Large capital-intensive firms tend to be more profitable than small ones, when conditions are good. However, when times are hard, small labour-intensive firms may find survival easier than large ones as they will find cost reduction easier.

Capital-intensive firms tend to produce standardised products, with low profit margins whereas labour-intensive firms are normally more customer focused, resulting in the opportunity to charge higher prices and obtain larger profit margins.

The bigger the market for a product, the more likely it is that it will be produced by capital-intensive methods. This has significant implications for the international market. Firms based in large markets, such as the USA, have a significant advantage over those that have developed in smaller national markets, such as Belgium or Luxembourg.

Cell production and teamwork

Changes in quality control methods and technological advances in recent years have led to a revolution in production methods. This revolution has been given the name of lean production. This term covers a range of new methods and procedures, which will be examined and summarised in this section.

Changes in quality control methods and technological advances in recent years have led to a revolution in production methods. This revolution has been given the name of lean production. This term covers a range of new methods and procedures, which will be examined and summarised in this section.

The purpose of lean production is to:

- Improve quality and lower rejection rates

- Increase productivity

- Reduce the costs of production by cutting aspects such as waste

At the beginning of this topic we examined various production methods, such as job, batch and flow production. Problems occur with many of these. For instance, flow production may lead to issues of poor morale, motivation and efficiency, as specialisation eventually deskills jobs and reduces work to monotonous, repetitive and simple actions. Little judgement and responsibility is afforded the employee. To remain competitive, firms desire the production of quality product at as low a cost as possible. To ensure consistent and reliable quality, at a fair cost, traditional mass production has been replaced by alternative methods of managing and operating assembly lines. These include:

- Cell production

- Just-in-time (JIT) production

Cell production

Cell production

Cell production is an important ingredient of lean manufacturing and refers to a manufacturing system where the workforce is divided into self-contained teams designed to complete a particular manufacturing process or product. The team is responsible for quality control and 'sells' the part-finished product to the next cell which is regarded as an 'internal customer'. Each member of the team is multi-skilled, allowing for greater flexibility in production through job rotation.

With cell production, assembly lines are broken down into groups of related activities, not individual ones. The cell is normally arranged in a 'U' or horseshoe shape. Each self-contained team (cell) is responsible for the completion of a product or specific process. Every member of the team is skilled at a number of roles, so providing an opportunity for job rotation. It is necessary to locate all the different equipment needed to manufacture the product together in the same production area.

The team is responsible for allocating specific roles, covering for absences and holidays, appointing their own supervisors, organising training and arranging their own breaks. They are responsible for the quality of the 'product' they pass to the next team, who are regarded as internal 'customers', which is a key element in the Kaizen approach to quality control. In effect, they operate their own little assembly factory. Each cell is responsible for a complete unit of work, which Herzberg identified as a method of job enrichment.

This method gives employees some say in their work; hence improving motivation and morale; they are less likely, therefore, to become bored by repetitive work. Those that want to can take responsibility. This form of team working has become increasingly popular as it combines the advantages of mass production with a human system, which is more motivating than the traditional assembly line.

Firms may go one stage further and train teams responsible for manufacturing the entire product - the teams then move around the plant or factory with the product and complete each stage of production. This should improve motivation as employees are empowered, resulting in quality benefits.

The objective of cell production is to enable greater flexibility to produce a high variety of low demand products, while maintaining the higher productivity of larger scale production.

Advantages of cell production:

- stability of the team improves communication between the cell members

- processes, defects, scheduling and maintenance can be managed more efficiently and cost-effectively

- workers become multi-skilled and are consequently more adaptable and flexible to the changes in the business

- seeing the product from start to finish may create greater 'pride' and job satisfaction

- staff feel more involved in decision-making and the variety of work and greater responsibility generally results in better motivation

- quality improves because each cell has 'ownership' over production and cells often aim for 'zero defects' and the elimination of waste ('Muda')

- low stock requirements and minimal work-in-progress allows for the operation of a just-in-time (JIT) system

- improved customer response time

Disadvantages of cell production:

- may not allow firms to use their machinery as intensively as in flow production and output will be lower than mass production as a result

- greater investment is required in new management and control processes, such as stock ordering

- there may be rivalry between different cells and conflict may arise if one cell is left to wait for output from another

The following article from the engineering review magazine outlines not only a cell production system, but how this is being adapted to allow robots to take over the roles of human workers on the assembly line in the IHI group of companies in Japan. Follow the link below to view the article; then undertake the exercise.

Prepare a short report explaining how it is becoming possible to apply industrial robots to

tasks that cannot easily be automated and which presently rely heavily on human workers.

Cell production - examples and illustrations

Modern car assembly - the modern assembly line

At first glance, a modern car assembly line looks similar to the old 'Henry Ford' production process. However, deeper examination will reveal significant differences. Although individual tasks are small and relatively simple, the production line is now made up of a series of consecutive work 'cells', which have:

At first glance, a modern car assembly line looks similar to the old 'Henry Ford' production process. However, deeper examination will reveal significant differences. Although individual tasks are small and relatively simple, the production line is now made up of a series of consecutive work 'cells', which have:

- A team of workers

- A supervisory responsibility

- A quality responsibility

- A process/product quality improvement responsibility

The team, or cell, decides who does what within the team. It decides how jobs will be rotated to relieve boredom, or to ensure the relevant specialist is available for certain tasks. The cell works as a team, not a number of individuals.

Each cell will pass a 'product' onto the next cell in the line and is responsible for seeking improvements in processes and quality. Cells normally operate as quality circles, which we examine later in this topic. It is almost certain that just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing will be in place.

The purpose of using cells and JIT production is to combine the advantages of a tailor-made, individual car of high quality - produced by job production - with the benefit of mass production savings. When consumers go to a dealer and place an order, a personal code/reference number and production slot is allocated at the same time. In other words the vehicle is made-to-order, but not using job production. These changes mean that car prices, in real terms, have fallen and fallen, but quality has steadily improved.

Nihon Kohden

Read about the assembly process at Nihon Kohden, Japan's leading maker of EEG, patient monitors, AED, and medical electronic equipment, describing its use of cell production and quality assurance.

You can view the article, Our commitment to safety and quality, in the window below or follow the previous link to read the article in a separate window.

Changing the production system

If you would prefer to view this interaction in a new web window, then please follow the link below:

Read the article Daimler and Aston Martin to Collaborate on High-End Maybachs and Lagondas (you can do this in the window below or follow the previous link to read the article in a separate window) and then answer the questions below.

Analyse the implications for marketing, human resource management and finance that might arise for Daimler as it moves from to mass to batch production for its Maybach brand.

Selecting the most appropriate method of production

There is no one best method of production. The choice of production method rests on a number of variables which will change over time. The following are some factors which will influence business in its selection of production method:

- The level of demand - if there is a mass market for a product, this may justify the investment in capital to allow for flow production.

- The nature of the target market - customers may demand a high level of customisation and quality which only job production can provide. However, price sensitive markets segments may only be satisfied if the firm produces high volume, standardised products.

- The nature of the product - certain products may only be produced by one production method. Unique constructions, such as sky scrapers and sports stadiums will require job production.

- The comparative costs of labour and capital - labour is often the largest cost for firms in developed countries. Consequently, large firms will look to minimise cost by investing in automation and mass production technologies. However, businesses operating in countries where labour is relatively cheap are more likely to use labour-intensive production methods.

- The nature of the firm itself - small firms are unlikely to have the funds to invest in the capital required for mass production.

- New technologies - as technologies develop, they often become cheaper. This may allow smaller firms to acquire the capital required for batch or flow production systems.

- The goals of the business - firms seeking to maximise market growth and/or profitability, may invest in flow production, whereas firms aiming for a high quality niche may build on unique selling points, such as 'hand-made' or 'customised' requiring job production methods.

- Government policies - government often attempt to stimulate economic growth by offering grants, subsidies and tax breaks for capital investment. Some firms will be persuaded to make production more capital-intensive as a result.

Combining methods of production

The factors that affect the choice of production method are also likely to encourage firms to use a variety of production methods to satisfy the needs of customers in different market segments.

The burger, or fast food market, tends to work along the principles of batch production with a number of identical burgers being produced at a time. However, where demand is lower for certain products, e.g. vegetarian burgers, these may be made to order, i.e. job production.

The burger, or fast food market, tends to work along the principles of batch production with a number of identical burgers being produced at a time. However, where demand is lower for certain products, e.g. vegetarian burgers, these may be made to order, i.e. job production.

Subway, for instance, produces batches of rolls or 'subs', but consumers are able to customise the fillings to a certain extent within the options available.

Mass production can be customised through the use of greater automation and robots in the production line. Until recently, assembly lines were built on the principle of the standardisation of products. Under this production method, any change in the nature of the finished product would require the line to be stopped, new tools or materials added and/or existing equipment to be recalibrated. However, robotic technology may be programmed to produce varying sizes and finishes. Paints, for example, can be changed rapidly by the rotation of nozzles.

The technology market in particular combines methods of production. Dell traditionally sells online and customers can order a number of standardised products, which are produced using assembly line operations. However, during the order process, additional options can be selected. This additional flexibility may threaten the existence of smaller firms which do not enjoy the lower costs associated with mass production, but whose greater choice and flexibility to meet customer needs previously justified the higher price they inevitably charged.

5.1 Production methods - questions

In this section are a series of questions on the topic - Production methods. The questions may include various types of questions. For example:

- Self-test questions - on-screen questions that give immediate marking and feedback

- Short-answer questions - a series of short-answer questions to help you check your understanding of the topic

- Case study - a case study with associated questions

- In the news - questions based around a topical business news article

Click on the right arrow at the top or bottom of the page to work through the questions.

Methods of production - short answer questions

Question 1

Distinguish between job, batch and flow production.

Question 2

Explain why consistent quality is easier with flow production than with job production.

Question 3

Using appropriate examples distinguish between labour-intensive and capital intensive production.

Question 4

Explain why it is difficult to categorise the production method used by Dell computers.

Question 5

A local manufacturer of yachts starts out making a few boats using job production. As its popularity grows it switches to batch production. Finally, it becomes an international firm and produces a large number of yachts using flow production.

Examine the likely effects of these changes in operation on quality, price and choice.

Cell production and teamwork - short answer questions

Question 1

Define the term 'cell production'.

Question 2

Identify the advantages and disadvantages of introducing cell production.

Question 3

Explain why cell production leads to improvement in overall quality.

Toyota redefines auto assembly line

Read the article Toyota redefines auto assembly line (you can do this in the window below or follow the previous link to read the article in a separate window) and then consider answers to the questions below.

To help answer the following questions, you may also wish to read:

Question 1

Define the terms:

- assembly line

- innovation.

Question 2

Explain the implications for Toyota of 'increasing demand for low-price vehicles in emerging economies, while sales in industrialized nations remain sluggish'.

Question 3

Analyse the implications for marketing, human resource management and finance that arise from changing to Toyota's new assembly line system.

Question 4

Evaluate the impact on Toyota of the world recession and the Yen's steep appreciation.

5.2 Costs and revenues - notes

In the previous section we looked at production methods. We will now examine costs and revenues.

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Define, explain and give examples of each different type of cost

- Explain the meaning of revenue and comment on possible sources of revenue for different firms

- Explain and calculate the contribution to fixed costs

- Explain the nature of cost and profit centres

- Analyse the value of cost and profit centres to a firm

- Analyse the role of contribution analysis in determining the viability of each product for a multi-product firm

Costs and revenues

The terms 'revenues' and 'costs' are probably two of the most important concepts in Business and Management. No business can make profit without sales revenues and cost control is vital to a business if it is to maintain and improve profitability.

In simple terms, a business wishing to make a profit must make sufficient revenues to cover its costs because:

![]()

Revenue

Revenue

For a firm, revenue is the total amount of money received for goods sold or services provided during a certain time period. Revenue is shown usually as the top item in a profit and loss statement from which all charges, costs, and expenses are subtracted to arrive at net profit.

Revenue is also known as sales, sales revenue or turnover. It should be distinguished from other forms of income that a firm generates from other non-operational activities, such as the sale of assets.

Total revenue can be expressed by the following formula:

![]()

![]()

A firm's performance will be judged by how much profit it is able to make from a given sales revenue. The higher the proportion of profit, the more efficiently the firm is being run, as by implication the costs of the business must have been minimised to increase profit levels.

Fortune magazine produces annual rankings of the largest 500 global corporations, listing sales and profits.

Read the article Fortune's Global 500 ranking (you can do this in the window below or follow the previous link to read the article in a separate window)

Of the top ten businesses in the table, which is the most efficient in terms of turning revenues into profit? In other words, which has the highest profit margin?

In the following sections we will examine the nature of revenues and costs in greater detail.

Types of costs

To be able to control costs, it is necessary to understand more about them and from where they arise. In this section we examine the nature and classification of costs.

Costs are usually classified according to their relationship with the level of output of the firm. The following costs are therefore defined in relation to how they change in value as the level of output varies.

Fixed costs

Fixed costs

Fixed costs are costs that do not vary with the level of output in the short term.

Examples of fixed costs

- Rent

- Office salaries

- Advertising

- Insurance

- Depreciation

Fixed costs can be represented on a graph and this would appear as follows:

Figure 1 Fixed costs

A common mistake made by candidates in examinations is to state that fixed costs will always remain constant. This is not the case, as these costs are fixed with respect to short-term changes in the level of output only. In the long-term, a firm may rent a second factory or take out more insurance cover, so fixed costs are likely to change.

Variable costs

Variable costs

A variable cost varies in direct proportion with the level of output. Varying directly means that the total variable cost will be totally dependent on the level of output. If output doubles, then the variable cost would double. If halved, the variable costs would halve. If output were zero, then no variable costs would be incurred.

Common examples of variable costs are as follows:

Example of variable costs

- Direct labour

- Raw materials and components

- Packaging costs

- Royalties

Variable costs can be represented on a graph and this would appear as follows:

Figure 2 Variable costs

Semi-variable costs

Semi-variable costs

A semi-variable cost is an expense, which includes a mixture of fixed and variable components. These costs vary (change) with output, but not in direct proportion The fixed cost element is the part of the cost that must be paid irrespective of the level of activity. On the other hand the variable component of the cost is payable proportionate to the level of activity. These costs are sometimes called mixed costs. In some cases, costs may be fixed for a set level of production, becoming variable after that level is exceeded.

In reality, nearly all costs cannot easily be classified into either fixed or variable. Most costs will fall somewhere between the two classifications. In this case, we classify these as semi-variable costs.

For example, although the wages of the production staff may appear to be variable costs, in reality, they will vary with the level of output, but not in a direct manner. The direct relationship is unlikely to hold over a long period of time. Similarly, many costs will have a fixed element, but also a variable element (for example, most bills for gas and electricity will consist of a standing charge, which is fixed and a variable element, which will depend on the usage). Telephone bills often contain a fixed line rental, but call charges vary with the number made, the distance of the call and the time elapsed. A telephone bill will aggregate these different charges.

What would the graph of a semi-variable cost look like?

As there is a link between the cost and the level of output, we would expect the semi-variable cost curve to be upward sloping. However, there is no accurate 'textbook' appearance for this curve. It will normally slope upwards in a non-linear manner, although this may be stepped or curved.

Examiners find the concept of semi-variable costs particularly difficult to integrate into examination questions - particularly break-even analysis - so semi-variable costs are often ignored, even though they are normally the most common cost.

Total costs

Total costs

Total costs are the sum of fixed costs, semi-variable costs and variable costs for any particular level of output. If the output level is zero, then total costs would consist only of fixed costs.

In nearly all cases, total costs will be the addition of total fixed costs and total variable costs (where total variable cost is the variable cost per unit multiplied by the level of output).

Total variable costs = variable cost per unit x output level

Total costs = fixed costs + variable costs

Total costs can be represented on a graph and this would appear as follows:

Figure 3 Total, fixed and variable costs

Direct costs

Direct costs

A direct cost is similar to a variable cost in that it compares the cost with the level of output. However, a direct cost is any cost, which is directly related to the output level of a particular product or department. Direct cost is more appropriate for a firm that makes more than one type of product.

For example, assume a firm is producing both chairs and tables. The chairs produced use a certain type of wood, but the tables use another type of wood. Then both types of wood would be direct costs, because they are directly related to the level of output of a particular product, not to the level of output in general.

Indirect costs

Indirect costs

An indirect cost is any cost, which cannot be linked with the output of any particular product or department. These costs are also known as indirect overheads or administrative costs. They are related to the level of output of the firm, but not in a direct manner and not for any one product.

For example, the cost of powering machinery will be related to the level of output, but not to a particular product.

Generally, the terms indirect and direct costs are more likely to be used when the firm produces a range of products. In break-even analysis, the firm will only be producing a certain product type. This means that the terms fixed and variable costs are more likely to be used.

Costs - task

Now, a task for you that will check if you understand the new terms you have just met.

Imagine that you have decided to start a business, Student Enterprises Ltd, offering a home delivery service for DVD's. You are next door to a large rental firm who are prepared to supply you, so you will not have to buy stock yet. What would you have to spend money on to set the business up and then operate it?

Make a list of all the costs that you can identify. Examine the list you have made, and then classify the costs between fixed and variable costs. When you have done this, click Costs for Student Enterprises Ltd.

A final question; what type of cost is labour?

The answer here starts with a phrase that is very common within business and management. The answer starts with - 'It all depends'. It all depends on how the labour is paid. Make a list of as many payment schemes (different ways people are paid) as you can think of, then click on Remuneration. Look up the term in the glossary as well.

This means that for much of the time labour is a fixed cost, fixed for the period of the employment contract. Relatively few people are paid solely on the basis of what they produce. Most employees have elements of both fixed and variable payments in their remuneration.

You will often be asked to give examples of fixed and variable costs. When answering this type of question, it may be best NOT to use labour as an example.

Costs and revenue - shape of cost curves

Figure 1 below shows how average costs change as output increases. As you can see from the diagram, average cost falls as the firm increases its output and moves towards its capacity.

What determines the actual shape of this cost curve?

Figure 1 Average cost curve

The answer is the distribution between fixed and variable costs. Let's examine two situations - where fixed costs are a very high proportion of total costs, and where they are a low proportion.

Fixed costs are a high proportion of total costs

This type of firm would be described as being capital-intensive. A good example is a scheduled airline where most costs are fixed, at least in the short to medium term. It would have a cost curve as follows:

Figure 2 Total costs - capital-intensive firm

Total costs would vary little with changes in capacity, but average costs, however, would be very sensitive to output. Look at the diagram below:

Figure 3 Average cost - capital-intensive firm

Average costs would change significantly as the numbers of passengers increase or decrease. Profits or losses would be very sensitive to capacity; in other words the number of seats sold.

Fixed costs are a low proportion of total costs

This is the reverse of the above. Any such firm would be considered to be labour-intensive. An example would be a market stall selling fruit and vegetables. Its cost curves are as follows:

Figure 4 Total cost - labour-intensive firm

Costs vary considerably with output, or capacity. The average cost curve now is very different to that of a capital-intensive firm. Look below:

Figure 5 Average cost curve - labour intensive firm

Average costs are less sensitive to changes in output.

Costs - fixed and variable - examples

Full service or low cost airlines

All airlines, as with any other business, try to maximise income and minimise costs.

As was seen earlier, airlines have very high fixed costs. Let's look at this in more detail. We will compare full service national operators such as Lufthansa with the low cost firms, such as Ryanair. What are the costs that are incurred for a flight?

| Full cost | Low cost | |

|---|---|---|

| Cost of the AEROPLANE | FC | FC |

| Crew costs | FC | FC |

| FUEL COSTS - empty of passengers | FC | FC |

| FUEL COSTS - as load increases | VC | VC |

| Catering costs | FC | VC |

| Landing charges | FC | FC |

| Handling charges | FC | FC |

| Ticketing costs | FC | FC |

| Commission to travel agents | VC | None |

Revenue

Revenue is a business term for the amount of money that a firm receives from its ordinary activities in a given period, mostly from sales of products and/or services to customers. In other words this is operational revenue as it is the result of a firm's normal selling activities. Revenue is recognised either when the cash is received OR at the point of sale (if the goods are sold on credit). Revenue is also known as:

- Sales

- Sales revenue

- Sales turnover

Revenue is basically "price x quantity" (the price for one item multiplied by the number of items sold), summed over all goods; if the price per unit varies with the quantity, then for each price per unit this multiplication is done, and the results are summed.

Revenue arises from sales made in cash and sales made on credit and must not to be confused with the term 'profits', which require costs to be deducted from revenues. Profit is calculated using total sales revenue, but it is important to understand the significance of credit sales. Sales turnover recorded in the profit and loss account includes credit sales and therefore profit is based on this figure. However, credit sales do not involve any cash transfer, so a firm's profits may appear to be healthy even if their liquidity (cash) position may not be so healthy, since the customer is yet to pay.

There are a number of different sources of income a firm may receive. Operational income (revenue) includes:

- cash sales using money, cheques or debit card

- credit sales (i.e. where the business has sold goods to customers, but has not yet received the cash)

A business may receive non-operational (non-sales) income from other activities and sources. Technically these incomes are not revenue, although it is quite common for these to be referred to as such. These incomes may include:

- interest received from cash deposits in financial institutions, such as banks

- royalties received for allowing other businesses to use their ideas

- dividends that the business receives on shares held in other companies

- fees for hiring-out the resources of the business to a third party

- grants from government for conducting certain qualifying activities, such as setting up a new business

- sponsorship from another organisation for promoting or displaying its brand name

- donations made to non-profit organisations of charities (NGOs) by personal or institutional donors

Mattel 1Q Profit Falls On Higher Expenses

Mattel

Read the article Bratz lawsuit takes toll on Mattel profit, (you can do this in the window below or follow the previous link to read the article in a separate window) and then consider answers to the questions below.

You may also wish to read the following articles before you attempt the questions below:

Question 1

Question 1

Define the terms:

- revenue

- expenses.

Question 2

Explain the reasons why Mattel's sales revenues rose 8%, but its profits fell 33%.

Question 3

Analyse the implications for Mattel of its dispute with MGA manufacturer of the rival Bratz dolls.

Question 4

Evaluate Mattel's strategy of maintaining a diverse portfolio of products and countries.

Costs and decisions

Most firms make more than one product and so may have trouble allocating fixed costs to the products (see the next section on multiproduct firms). One alternative to dealing with this issue is not to allocate a proportion of fixed costs to each product line product at all, but to employ the concept of contribution.

Contribution to fixed costs

To make a profit, the price charged for a product or service must cover both fixed and variable costs. Contribution really is shorthand for the term 'contribution to fixed costs and overheads'. If average variable cost is deducted from the unit price the amount left is a contribution to fixed costs.

Contribution is the difference between price and the direct, or variable costs, of a product or service.

![]()

For a multi-product firm, total contribution can be calculated by the formula:

![]()

A product is worth making and selling if it makes a contribution to fixed costs. Since fixed costs have been paid already, any contribution is better than nothing. In this form of costing, fixed costs or overheads are treated as a cost centre. This makes them visible rather than hiding them in a notional product cost.

Let's look at Low Fidelity Ltd. It produces DVD players and DVD units for computers. The firm knows the following financial details:

| Fixed costs | $100,000 per week | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable costs | DVD | $50 per unit |

| Computer units | $65 per unit | |

| Selling price | DVD | $220 each |

| Computer units | $180 each |

DVD's make a contribution of $170 each and the computer units $115 each. The profits cannot be divided between the products. The total profit made by the firm is known, however, as is the contribution each product line makes.

Contribution example

| Contribution analysis - Student Computers plc - sales Units $'000's |

|---|

| Product | A | B | C | D | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 2,000 | 3,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | |

| Variable costs | 500 | 2,000 | 1,500 | 500 | |

| Contribution | 1,500 | 1,000 | 500 | 1,500 | 4,500 |

| Overheads | 4,000 | ||||

| Profit/(Loss) | 500 |

Any or all of the following will increase profits:

- Increasing sales of products

- Decreasing unit variable costs

- Reducing overheads.

Contribution can also be calculated on a per unit basis and used in the same way, for example:

| Contribution analysis - McDonalds Soups plc |

|---|

| Variety | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price per unit | 10.50 | 8.75 | 12.54 | 22.75 | 13.45 | 10.00 | 26.45 |

| VC per unit | 5.25 | 1.36 | 4.27 | 11.75 | 6.75 | 5.00 | 12.00 |

| Contribution per unit | 5.25 | 7.39 | 8.27 | 11.00 | 6.70 | 5.00 | 14.45 |

All are worth making since they all have a positive contribution. Soup variety F, however, is the most vulnerable if McDonalds Soups is looking to rationalise its product range.

Overhead costs are thus put under the microscope.

Contribution analysis for multi-product firms

Calculating the profitability of a product relies on the firm being able to establish the costs that it incurs in production. However, firms that manufacture more than one product may do so in shared facilities. For example, a firm may have one factory containing three product lines. For each product, it may be possible to identify exactly the amount of raw materials being used, the cost of the employees working on that line and additional costs such as transport and packaging. These direct costs can be deducted from the revenues that product earns. However, what does the firm then do with the bills for utilities, such as electricity, water and gas? Even more problematic are back-office expenses, such as the salaries of support staff in IT, Marketing or Human Relations departments - how are their salaries allocated?

Calculating the profitability of a product relies on the firm being able to establish the costs that it incurs in production. However, firms that manufacture more than one product may do so in shared facilities. For example, a firm may have one factory containing three product lines. For each product, it may be possible to identify exactly the amount of raw materials being used, the cost of the employees working on that line and additional costs such as transport and packaging. These direct costs can be deducted from the revenues that product earns. However, what does the firm then do with the bills for utilities, such as electricity, water and gas? Even more problematic are back-office expenses, such as the salaries of support staff in IT, Marketing or Human Relations departments - how are their salaries allocated?

Contribution analysis works on the principle that any division of these costs is likely to be arbitrary and inaccurate. For example, any employee working in marketing would have to record every minute spent working on the marketing of a particular product so that the correct proportion of his/her salary could be charged to that product. However, how would the charge be made if the employee was working on a promotion for the firm itself, rather than a particular product?

Contribution analysis adopts the principle that only the costs directly attributable to a product will be allocated and deducted from revenue and that the remaining figure is that product's contribution to the unpaid fixed and indirect costs (overheads). To calculate whether a multiproduct firm makes a profit overall, the contributions for every product are totalled and then compared to the unpaid fixed and indirect costs.

The following formula is then used to calculate the firm's profit:

Profit = Total contribution - (Total fixed costs + total indirect costs)

Using this method of unapportioned fixed costs and indirect costs means that a product may be retained as long as it makes a positive contribution.

This method of costing can be used for the following:

- Setting of product priorities - the products with the highest contribution are considered the most viable and given the highest investment/marketing priority. Look again at McDonalds Soups. Soup variety G makes the greatest contribution per unit, so should be supported. However, add quantities and the picture might change.

| Contribution analysis - McDonalds Soups plc ($) |

|---|

| Variety | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price per unit | 10.50 | 8.75 | 12.54 | 22.75 | 13.45 | 10.00 | 26.45 |

| VC per unit | 5.25 | 1.36 | 4.27 | 11.75 | 6.75 | 5.00 | 12.00 |

| Contribution per unit | 5.25 | 7.39 | 8.27 | 11.00 | 6.70 | 5.00 | 14.45 |

| Sales (units) | 1,000 | 500 | 900 | 200 | 1,200 | 3,500 | 250 |

| Contribution | 5250 | 3695 | 7443 | 2200 | 8040 | 17500 | 3612.5 |

The situation appears very different once demand is factored into the analysis. Soup variety F now appears to be the best proposition.

- Product portfolio management - any new product will have to earn more contribution than the one it replaces. However, the contribution used (unit or total) will affect the result as illustrated above.

- Make or buy decisions - these are decisions about whether the firm should produce goods themselves or buy them in.

- Acceptance of special orders - this method helps firms, which do not usually use contribution costing, come to a decision on whether to supply at a price different to the one it normally charges (see next page for further details).

Special orders

Let's look at an example of the last option from the previous page - acceptance of special orders:

Computers for Germany - special order

Student Computers plc. has received an order for 500 computers from a University in Germany, which is not one of their regular markets and is not included in their sales plan. The computers normally sell for $500, but the German University is only prepared to pay $350. The cost structure of the product is shown as:

| Price | $500 |

|---|---|

| Variable cost | $200 |

| Allocated overheads | $200 |

| Profit | $100 |

The view of some managers is that they should refuse the order since they will make a loss of $50 per computer if price is only $350 instead of the normal $500. However, because it is a special order all the overheads are already allocated. This means that the computers will make a contribution of $150 each to fixed costs. On this basis, the order should be taken on financial grounds, as this contribution is actually profit as fixed costs have been paid.

The view of some managers is that they should refuse the order since they will make a loss of $50 per computer if price is only $350 instead of the normal $500. However, because it is a special order all the overheads are already allocated. This means that the computers will make a contribution of $150 each to fixed costs. On this basis, the order should be taken on financial grounds, as this contribution is actually profit as fixed costs have been paid.

There may still be grounds for refusal, though. Will the order and its lower price:

- encourage existing customers to expect a similar reduction in price?

- set a precedent for future sales?

- affect brand image?

If the answer to any of these questions is 'yes', it may be wise to refuse the order, or at least try to negotiate a higher price.

Cost centres and profit centres

Previously, we met the concept of budgets and variance analysis. These are part of the management accounting function within a company. Financial plans are used to predict what will happen, and become the basis for action where necessary. They are rather like the data used when navigating a ship or aircraft. They measure and report where a company is, and enable the management to plot a course, so that it arrives at its financial destination.

If a firm is to maximise profit it needs effective financial management. Forecasting and controlling revenues and expenditure is the basis for this financial planning. The difference between the total revenues and total cost is the profit. If the firm is large the management of revenues and costs is likely to be complex, so the firm is often divided up into a series of departments, or cost and profit centres to simplify the process and to support more micro-analysis. Cost and profit centres can be isolated financially with individual managers held responsible for costs incurred, and revenues generated.

The concepts of profit and cost centres underpin effective financial management.

Profit centre

A profit centre is a division, or part of an organisation, where costs and revenues can be clearly identified, isolated and recorded allowing the profit it generates to be determined. The profit centre should be under the control, or responsibility, of one manager.

Cost centre

A cost centre is a division or part of an organisation that generates costs which can be clearly identified, isolated and recorded, but is not directly producing revenues so profit cannot be determined. The cost centre should be under the control, or responsibility, of one manager.

Examples of profit/cost centres:

Examples of profit/cost centres:

- departments

- products

- factories

- groups of machines

- locations e.g. regional offices

- functions

- sections

- individuals

For example a school may be both a profit and a cost centre. If a school is privately run and part of a consortium or group of schools, and students (or their parents) are charged fees, the school generates revenues and costs. The profit can be calculated for each school in the consortium and performance measured. However, identifying profit centres within schools is more problematic. Can a department be a profit centre? This would be difficult unless a notional fee is established for a particular course or subject to calculate total revenues. It is more likely that departments within schools, both in the profit and non-profit sectors, will be considered cost centres. Costs can be identified in terms of teacher wages and the costs of equipment and materials used in that department. Most departments are allocated a budget which provides responsibility and accountability.

One advantage of cost centres is that the firm is not concerned if costs are fixed or variable. If it is a cost, then it belongs in a cost centre.

The purpose of creating cost and profit centres is to develop a financial system where there is direct responsibility and accountability. For this to be an effective system, there must also be authority. In other words, the person managing a cost or profit centre must also have the authority to change things and make decisions, as well as carrying the responsibility when things go wrong.

NO ACCOUNTABILITY WITHOUT AUTHORITY

All divisions of an organisation are potentially cost centres. Examples are production, personnel, accounts, and transport. A few, however, are profit centres as well. Examples are the sales department or, if the firm is organised that way, individual brands.

Why have cost and profit centres?

Cost and profit centres have three main purposes:

- Financial accounting. They enable a firm to see how it is performing in comparison with budgeted figures.

- Motivational. By giving staff targets, and also delegating authority, they are motivated to do well. Departments and smaller teams tend to be more effective than larger business groupings. They may be rewarded for good performance, and helped to avoid poor results. Responsibility must be linked to the necessary authority.

- Organisational. By breaking the firm down into manageable chunks, senior management can monitor performance and identify strong and weak areas in the organisation. As a result it can focus production on particular units. Management time can then be concentrated on the areas where it is required and not wasted where it is not.

If a firm is broken down into cost and profit centres with agreed budgets, and carefully monitored using tools such as variance analysis, the firm possesses a powerful controlling mechanism. Used constructively, senior management have the means to identify high performing parts of the business and those which needs attention. It also provides a means of measuring and assessing staff and rewarding them accordingly.

Effective use of cost centres means that no part of an organisation will be hidden or unaccountable. All overhead departments, or STAFF FUNCTIONS, are clearly recorded and accounted for. Once this is revealed it is often possible to make considerable savings, and thus increase profits.

How the system is used will depend on the style of management adopted by the firm. This is another link to the human resource function and motivation. Business really is an integrated subject!

However, there are potential problems and issues associated with operating cost and profit centres:

- The allocation of costs, particularly overhead costs, is problematic. The method chosen for allocation will affect the level of costs apportioned and so influence apparent efficiency and profit levels.

- The performance of cost and profit centres can be influenced by external factors outside of the control of the managers running them, such as rising raw material and energy prices.

- They may encourage competition and conflict, especially where remuneration is affected by performance and profit levels.

- The pressure on cost and profit centres to cut costs may exclude consideration of ethical issues and result in organisations that perform well in terms of financial measures, but which fail to meet CSR targets.

Apportioning costs to profit and cost centres

When considering contribution costing, we identified the arbitrary nature of trying to allocate fixed and indirect costs to products in a multi-product firm and examined the salary of an employee in marketing department. Contribution analysis is based on the principle that unless a cost is directly attributable to a product, it should not be apportioned.

When considering contribution costing, we identified the arbitrary nature of trying to allocate fixed and indirect costs to products in a multi-product firm and examined the salary of an employee in marketing department. Contribution analysis is based on the principle that unless a cost is directly attributable to a product, it should not be apportioned.

However, many firms do attempt to allocate fixed and overhead costs. This may be as a way of making managers of departments and products aware of their responsibility for covering more than the direct costs of what they do. After all, the firm must pay for company-wide costs, such as administration costs, IT and rent, to establish whether it is profitable overall. The choice of method to allocate overhead costs will have a significant impact on the performance of each of a firm's cost and profit centres. The choice of method is at best quasi-scientific, and at worst subjective, because using one method may show a product is profit making, and using another method may indicate it is making a loss. Strategically, this could impact on whether a firm continues to sell a product or maintain a regional office.

Assume a factory produces 3 products A, B and C

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WORKERS | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| AREA (%) | 40 | 20 | 40 |

| SALES (% of total) | 30 | 30 | 40 |

| COMPUTERS | 20 | 40 | 40 |

The following costs apply to the business:

| $ | |

|---|---|

|

Direct costs (Variable costs) |

|

| Raw materials | 100 000 |

| Wages | 200 000 |

| Total VC/DC | 300 000 |

|

Indirect costs (Fixed costs/overheads) |

|

| Rent of factory | 40 000 |

| IT costs | 20 000 |

| Catering costs | 6 000 |

| Administration | 4 000 |

| HRM | 10 000 |

| Marketing | 20 000 |

| Total FC/IO | 100 000 |

DIRECT COSTS: these are the costs that can be directly related to a department or product e.g. wages and raw materials. It is easy to identify the cost of the raw materials used to produce A and those cost of the materials used to produce B and C. These costs can be allocated to each product. The same applies to wages. Assuming each worker earns the same, the cost to A is 100 workers multiplied by the individual wage. For B this is 50 workers and will be half of the cost for A.

INDIRECT COSTS: these are costs that are not directly related to the cost of producing an individual product. For instance, how is the factory rent of $40 000 divided between the three products? The firm could decide to divide this cost up in proportion to floor area - product A assumes 40% of the rent as it has 40% of the area, but B only 20%. However, the firm could also decide to divide it up according the ratio of sales, or by some other method.

Similarly how does the firm divide up the cost of the HRM department? This could be in the ratio of the number of workers of A B and C - 100:50:50 (2:1:1) or could be on area or sales.

Some choices for allocation may appear more sensible, but still may lead to inaccuracies.

Why? - Any allocation of costs to A, B and C is likely to be inaccurate. For example, the HRM department may spend most of its time dealing with the staff making product B and not product A, despite the fact that there are fewer staff in number.

However, it is necessary for someone to pay indirect costs as it is impossible to work out PROFIT until indirect costs are paid.

The most common methods of allocating costs are:

- Full costing

- Absorption costing

- Marginal costing

We consider each of these methods on the next few pages.

Full Costing

Full costing takes the overheads of the business and allocates them according to a single criterion. The firm may choose to allocate overheads using one of the following:

- Employees

- Area

- Sales revenue

- Output volumes

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $ | $ | $ | |

| Revenue | 200 000 | 160 000 | 170 000 |

| Direct costs | |||

| Raw materials | 30 000 | 40 000 | 40 000 |

| Wages | 80 000 | 60 000 | 60 000 |

| EMPLOYEES | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| AREA (%) | 40 | 20 | 40 |

| SALES (% of total) | 30 | 30 | 40 |

| COMPUTERS | 20 | 40 | 40 |

| Indirect costs (FC/IO) | $ |

|---|---|

| Rent of factory | 40 000 |

| IT costs | 20 000 |

| Catering costs | 6 000 |

| Administration | 4 000 |

| HRM | 10 000 |

| Marketing | 20 000 |

| Total FC/IO | 100 000 |

Allocation of fixed costs/indirect overheads in proportion with:

1. Employees (ratio 2:1:1)

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $ | $ | $ | |

| Revenue | 200 000 | 160 000 | 170 000 |

| Direct costs | |||

| Raw materials | 30 000 | 40 000 | 40 000 |

| Wages | 80 000 | 60 000 | 60 000 |

| Indirect costs | |||

| Employees (2:1:1) | 50 000 | 25 000 | 25 000 |

| Total costs | 160 000 | 125 000 | 125 000 |

| Profit | 40 000 | 35 000 | 45 000 |

2. Area ( ratio 2:1:2)

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| $ | $ | $ | |

| Revenue | 200 000 | 160 000 | 170 000 |

| Direct costs | |||

| Raw materials | 30 000 | 40 000 | 40 000 |

| Wages | 80 000 | 60 000 | 60 000 |

| Indirect costs | |||

| Area (2:1:2) | 40 000 | 20 000 | 40 000 |

| Total costs | 150 000 | 120 000 | 140 000 |

| Profit | 50 000 | 40 000 | 30 000 |

What these results show is that the choice of allocation using the number of employees or using the relative area dramatically affects the relative profitability. Product C goes from being the most profitable product using the workforce to allocate fixed costs/indirect overheads to being the least profitable using the production area.

Evaluation of full costing

All the overhead costs are totalled and then divided according to the selected criterion. This method is simple to use and, therefore, cheap to administer. It ensures that all the costs are allocated and paid for. However, it may result in some clear anomalies. For example, if the value of sales is used to allocate overheads, a small department of only 10 staff, but with high sales revenues, may be allocated the same charge for catering costs as much larger departments of several hundred.

Absorption costing

We have already said that fixed costs and overheads, such as heating and lighting, are not easily apportioned to specific profit/cost centres. These costs arise throughout the firm. However, they must still be paid for and absorption costing, like full costing, seeks to apportion these costs between the profit/cost centres.

Where full costing selects just one criterion as a means of allocation, absorption costing attempts to be more 'scientific' in the allocation, apportioning individual overheads using the most logical criterion.

Common methods of apportionment for a profit/cost centre include:

- Floor space

- Number of staff employed

- Value of machinery

- Sales revenue

- Direct labour hours worked

The method chosen should be appropriate to the type of overhead to be apportioned. For example, rent would probably be apportioned to the different cost centres based on the floor space of each cost centre. Whereas, HRM costs may be apportioned according to the number of people employed by each cost centre, since employees are the focus of the HRM department.

Example 1

The following data is available for Gray Ltd relating to their three cost centres.

| Machining | Assembly | Administration | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floor space | 50 sq m | 30 sq m | 20 sq m | 100 sq m |

| No of staff employed | 15 | 25 | 10 | 50 |

The overheads incurred are as follows:

| $ | |

|---|---|

| Heating costs | 10,000 |

| Canteen expenses | 25,000 |

It would seem appropriate to use the following bases for the apportionment of these overheads:

| Apportioned by: | |

|---|---|

| Heating costs | Floor space |

| Canteen expenses | No. of staff employed |

Have a go at apportioning the overheads for Gray Ltd and then follow the link below to see how you got on.

Example 1 - apportionment of overheads

Evaluation of absorption costing

Absorption costing is more complex than using full costing, but it is fairer in that the allocation of costs mirrors reality more closely, in that the usage of each product is taken into account. As such, the cost per unit of output is likely to be more accurate, and will inform pricing policy if a cost-plus policy is used.

However, the allocation of costs is still arbitrary to some extent and inaccurate. It is likely to be more time-consuming and costly than full costing or contribution costing methods.

5.2 Costs and revenues - questions

In this section are a series of questions on the topic - Costs and revenues. The questions may include various types of questions. For example:

- Self-test questions - on-screen questions that give immediate marking and feedback

- Short-answer questions - a series of short-answer questions to help you check your understanding of the topic

- Case study - a case study with associated questions

- In the news - questions based around a topical business news article

Click on the right arrow at the top or bottom of the page to work through the questions.

Cost centres and profit centres - short answer questions

Question 1

Explain the difference between a cost centre and a profit centre.

Question 2

Describe the difference between authority and responsibility.

Question 3

Explain two reasons for having cost/profit centres.

Question 4

Explain why a profit centre is also a cost centre, but not all cost centres are profit centres.

Question 5

Explain how a school can be a profit centre, but why department within it are normally cost centres.

Methods of costing - short answer questions

Question 1

Define the term 'contribution'.

Question 2

'A firm that makes more than one product does not know what they cost to make, but knows exactly how much profit the firm has made.' Discuss.

Question 3

Explain why contribution is as important to most firms as profit.

Question 4

Analyse the reasons why a firm may sell a product for less than its total cost of production.

Question 5

If you ran a supermarket, discuss how you could use the concept of contribution to maximise your profits.

Contribution costing - numerical questions

Question 1

Medallion Meats Ltd

Medallion Meats makes sausages in a single factory. It has a policy of having a range of 6 sausages on sale at any one time. Its Research and Development team has just developed two new varieties.

The Board has to consider the position at the next Board Meeting and decide which sausages it will sell for the next year and which sausages it will stop making.

You are the Brand Manager for sausages, and you are expected to recommend the new range to the Directors at that meeting. Considering the following data, prepare a Board Paper giving and supporting your recommendations.

E1 to E6 are the existing sausages and N1 and N2 are the new varieties.

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | N1 | N2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

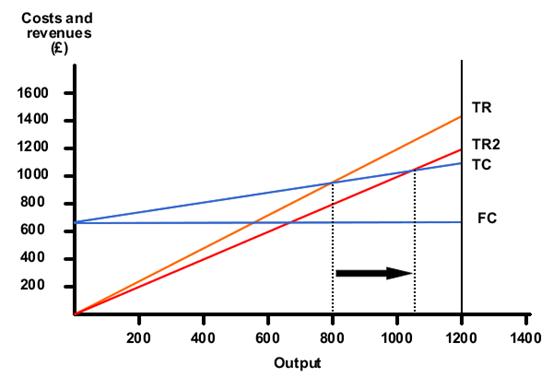

| Price | 10.50 | 12.70 | 13.80 | 9.27 | 15.80 | 26.10 | 13.20 | 32.50 |